-

What Is a Cyber Attack?

- Threat Overview: Cyber Attacks

- Cyber Attack Types at a Glance

- Global Cyber Attack Trends

- Cyber Attack Taxonomy

- Threat-Actor Landscape

- Attack Lifecycle and Methodologies

- Technical Deep Dives

- Cyber Attack Case Studies

- Tools, Platforms, and Infrastructure

- The Effect of Cyber Attacks

- Detection, Response, and Intelligence

- Emerging Cyber Attack Trends

- Testing and Validation

- Metrics and Continuous Improvement

- Cyber Attack FAQs

- Dark Web Leak Sites: Key Insights for Security Decision Makers

-

What Is a Zero-Day Attack? Risks, Examples, and Prevention

- Zero-Day Attacks Explained

- Zero-Day Vulnerability vs. Zero-Day Attack vs. CVE

- How Zero-Day Exploits Work

- Common Zero-Day Attack Vectors

- Why Zero-Day Attacks Are So Effective and Their Consequences

- How to Prevent and Mitigate Zero-Day Attacks

- The Role of AI in Zero-Day Defense

- Real-World Examples of Zero-Day Attacks

- Zero-Day Attacks FAQs

-

What Is Lateral Movement?

- Why Attackers Use Lateral Movement

- How Do Lateral Movement Attacks Work?

- Stages of a Lateral Movement Attack

- Techniques Used in Lateral Movement

- Detection Strategies for Lateral Movement

- Tools to Prevent Lateral Movement

- Best Practices for Defense

- Recent Trends in Lateral Movement Attacks

- Industry-Specific Challenges

- Compliance and Regulatory Requirements

- Financial Impact and ROI Considerations

- Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Lateral Movement FAQs

-

What is a Botnet?

- How Botnets Work

- Why are Botnets Created?

- What are Botnets Used For?

- Types of Botnets

- Signs Your Device May Be in a Botnet

- How to Protect Against Botnets

- Why Botnets Lead to Long-Term Intrusions

- How To Disable a Botnet

- Tools and Techniques for Botnet Defense

- Real-World Examples of Botnets

- Botnet FAQs

- What is a Payload-Based Signature?

-

What is Spyware?

- Cybercrime: The Underground Economy

-

What Is Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)?

- XSS Explained

- Evolution in Attack Complexity

- Anatomy of a Cross-Site Scripting Attack

- Integration in the Attack Lifecycle

- Widespread Exposure in the Wild

- Cross-Site Scripting Detection and Indicators

- Prevention and Mitigation

- Response and Recovery Post XSS Attack

- Strategic Cross-Site Scripting Risk Perspective

- Cross-Site Scripting FAQs

- What Is a Credential-Based Attack?

-

What Is a Denial of Service (DoS) Attack?

- How Denial-of-Service Attacks Work

- Denial-of-Service in Adversary Campaigns

- Real-World Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Detection and Indicators of Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Prevention and Mitigation of Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Response and Recovery from Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Operationalizing Denial-of-Service Defense

- DoS Attack FAQs

- What Is Hacktivism?

- What Is a DDoS Attack?

-

What Is CSRF (Cross-Site Request Forgery)?

- CSRF Explained

- How Cross-Site Request Forgery Works

- Where CSRF Fits in the Broader Attack Lifecycle

- CSRF in Real-World Exploits

- Detecting CSRF Through Behavioral and Telemetry Signals

- Defending Against Cross-Site Request Forgery

- Responding to a CSRF Incident

- CSRF as a Strategic Business Risk

- Key Priorities for CSRF Defense and Resilience

- Cross-Site Request Forgery FAQs

- What Is Spear Phishing?

-

What Is Brute Force?

- How Brute Force Functions as a Threat

- How Brute Force Works in Practice

- Brute Force in Multistage Attack Campaigns

- Real-World Brute Force Campaigns and Outcomes

- Detection Patterns in Brute Force Attacks

- Practical Defense Against Brute Force Attacks

- Response and Recovery After a Brute Force Incident

- Brute Force Attack FAQs

- What is a Command and Control Attack?

- What Is an Advanced Persistent Threat?

- What is an Exploit Kit?

- What Is Credential Stuffing?

- What Is Smishing?

-

What is Social Engineering?

- The Role of Human Psychology in Social Engineering

- How Has Social Engineering Evolved?

- How Does Social Engineering Work?

- Phishing vs Social Engineering

- What is BEC (Business Email Compromise)?

- Notable Social Engineering Incidents

- Social Engineering Prevention

- Consequences of Social Engineering

- Social Engineering FAQs

-

What Is a Honeypot?

- Threat Overview: Honeypot

- Honeypot Exploitation and Manipulation Techniques

- Positioning Honeypots in the Adversary Kill Chain

- Honeypots in Practice: Breaches, Deception, and Blowback

- Detecting Honeypot Manipulation and Adversary Tactics

- Safeguards Against Honeypot Abuse and Exposure

- Responding to Honeypot Exploitation or Compromise

- Honeypot FAQs

- What Is Password Spraying?

- How to Break the Cyber Attack Lifecycle

-

What Is Phishing?

- Phishing Explained

- The Evolution of Phishing

- The Anatomy of a Phishing Attack

- Why Phishing Is Difficult to Detect

- Types of Phishing

- Phishing Adversaries and Motives

- The Psychology of Exploitation

- Lessons from Phishing Incidents

- Building a Modern Security Stack Against Phishing

- Building Organizational Immunity

- Phishing FAQ

- What Is a Rootkit?

- Browser Cryptocurrency Mining

- What Is Pretexting?

- What Is Cryptojacking?

What Is a Dictionary Attack?

A dictionary attack automates the process of password guessing by cycling through a curated list of values — real words, leaked passwords, common character patterns, etc. The technique exploits weak authentication surfaces and scales easily across cloud-facing applications.

Capitalizing on poor password hygiene and weak credential policies, dictionary attack proves effective all too frequently. It succeeds where systems lack throttling, MFA enforcement, or centralized telemetry.

Attackers exploiting credential reuse don’t trigger traditional exploit defenses. In sprawling environments with hybrid identity systems, every successful guess can bypass perimeter controls, escalate access, and compromise internal services.

Dictionary Attack Explained

A dictionary attack is a cyber attack using a specific brute-force credential guessing technique that targets authentication systems using predetermined lists of potential passwords or passphrases. It falls under tactic T1110.001 — Brute Force: Password Guessing in the MITRE ATT&CK framework. Unlike general brute-force methods, which iterate through every possible character combination, dictionary attacks use human-generated values, such as:

- Words

- Keyboard patterns

- Common substitutions

- Previously leaked credentials

Attackers attempt dictionary attacks across the range of authentication points — login portals, APIs, SSH endpoints, remote desktop gateways — where input validation fails to detect abnormal login frequency or pattern abuse. The approach relies less on algorithmic sophistication and more on behavioral predictability in password selection.

Commonly associated terms include credential guessing, offline attack (when targeting password hashes), and password spraying (when attempting a single common password across multiple accounts). While credential spraying emphasizes breadth across users, dictionary attacks focus on depth against a specific account or secret.

Early Usage and Legacy Exposure

Early dictionary attacks targeted Unix shadow files and Windows SAM databases, using local hash files and rainbow tables to crack passwords offline. Attackers would steal the hashes then CPU-optimized tools like John the Ripper to iterate through dictionary files.

Attacks of this nature succeeded because of weak password creation policies and unsalted hashing. Despite advances in storage and authentication practices, dictionary-based guessing remains effective because humans still choose predictable credentials. Even in sophisticated environments, attackers continue to find fallback login pages, VPN concentrators, and unmonitored development portals. Entry is one oversight away.

Cloud Scale and Modern Variants

Today’s threat actors exploit API keys, CI/CD secrets, and federated login flows with dictionary attack techniques. Cloud IAM roles, SaaS administrator accounts, and DevOps credentials often become primary targets because they unlock lateral access and persistent footholds.

Attackers can source lists from breached databases, GitHub repositories, configuration leaks, and even language model outputs. With GPU-accelerated hash cracking and automated attack orchestration, dictionary attacks operate with speed and scale previously infeasible. The tactic now forms part of credential access campaigns alongside phishing, token theft, and session hijacking.

Dictionary attacks remain effective because password policies remain guessable and authentication telemetry remains disconnected from centralized detection logic. Any system that accepts user-supplied secrets is a candidate for enumeration.

How Dictionary Attacks Work

A dictionary attack succeeds by exploiting predictable inputs in authentication workflows. Attackers use curated lists crafted from years of human error, breach data, and linguistic patterns. The threat unfolds through precision automation, rather than brute force.

Automated Guessing Workflow

An attacker begins by identifying a target system that accepts user-supplied secrets, typically a login portal, API, or SSH endpoint. Using reconnaissance tools or DNS enumeration, they find public interfaces that expose authentication mechanisms. They then initiate the attack.

- Input selection: The attacker loads a dictionary file, often containing millions of potential passwords or phrases. Sources include rockyou.txt, custom-built lists, and dumps from data breach repositories like Have I Been Pwned.

- Credential injection: Scripts or tools such as Hydra, Burp Suite, Medusa, or custom Python scripts using requests iterate through combinations, sending login attempts at high velocity.

- Authentication abuse: Each request targets a specific login endpoint — such as /auth/login, /wp-login.php, or a cloud IAM interface — with crafted HTTP POST bodies. Headers mimic legitimate traffic to avoid basic detection.

- Success filtering: Tools monitor HTTP response codes, redirect behaviors, or API response bodies. Successful logins return distinctive artifacts — a 200 OK, session token, or multifactor challenge prompt.

- Persistence and escalation: After gaining access, attackers often test token reuse, privilege escalation, or lateral movement options. If MFA blocks access, they may pivot to phishing or token theft.

Tools and Infrastructure

Attackers don’t launch dictionary attacks manually. They rely on distributed infrastructure and purpose-built tooling:

- Credential attack tools: Hydra, Ncrack, Medusa, Patator

- Web interface brute-forcers: Burp Intruder, WFuzz, Gobuster

- Cloud-native scripts: AWS CLI brute-force modules, custom Boto3 scripts, Terraform state file enumeration

- Distributed execution: Botnets, compromised proxies, cloud VM fleets across regions (to avoid geo-throttling)

They may also use rotating user agents, random delays, or CAPTCHA solvers to bypass behavioral detection. Attack orchestration frequently runs in CI/CD pipelines or via remote control panels in initial access broker kits.

Exploited Weaknesses

A dictionary attack doesn’t need to exploit CVEs. It abuses design oversights and behavioral predictability across layers:

- Application layer: Weak rate limiting, predictable error messages, form validation bypasses, unthrottled login endpoints

- Network layer: Open SSH, RDP, or Telnet ports with poor segmentation and exposed credential services

- Cloud layer: Public S3 buckets with misconfigured access control, IAM users with login profiles, exposed API keys

- Human layer: Users reusing passwords, choosing patterns like Spring2024!, and ignoring password manager adoption

Web applications remain especially vulnerable when login error responses differ between incorrect usernames and incorrect passwords. That distinction leaks valuable signals to attackers.

Real-World Variants

In practice, dictionary attacks rarely stand alone. They feed into broader campaigns:

- Credential stuffing: A dictionary attack seeded with breached username-password pairs

- Phishing payload testing: Attackers use dictionary attacks post-phishing to validate stolen credentials

- Cloud reconnaissance: Tools like S3Scanner test for access to cloud buckets using known key patterns

- CI/CD compromise: Attackers scan .env or config.yaml files in public GitHub repos and try the secrets they find against service endpoints

For example, an attacker might, for example, locate an exposed Jenkins instance, extract credentials.xml, and run a dictionary attack against each user credential with known password patterns or default Jenkins secrets.

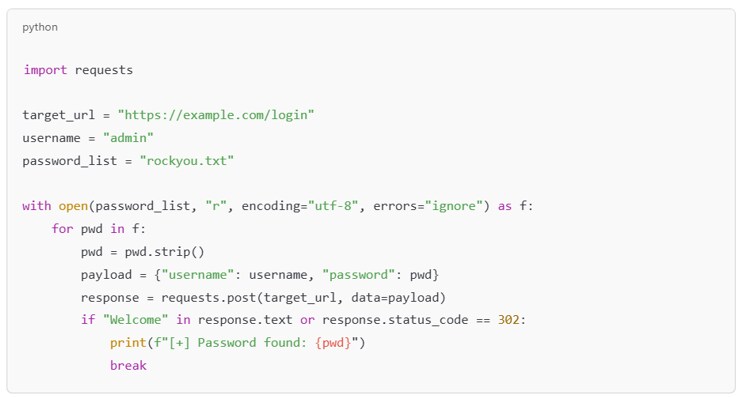

Figure 1: Sample Python script with request

A more advanced script would randomize headers, introduce time delays, and log failed attempts without blocking on each request.

Dictionary Attack in the Attack Lifecycle

A dictionary attack typically operates as a precursor, an enabler, or an augmentation within broader adversary workflows. Its simplicity masks its strategic utility — attackers use it to gain footholds, validate compromised credentials, or brute-force low-visibility access points in parallel with more complex tactics.

Role in Initial Access

Most dictionary attacks serve as an entry point. With the goal of breaching a single account, threat actors target exposed authentication services such as web portals, remote access tools, or API endpoints. When attackers find valid credentials, they gain an authenticated session without triggering exploits or executing payloads.

Initial access via dictionary attack offers several advantages:

- Low noise when distributed across IPs or blended with real user traffic

- Bypass of malware detection — no shellcode or binary delivery involved

- Built-in privilege when targeting admin panels, SaaS superusers, or service accounts

Common targets include WordPress admin panels, OpenVPN login forms, GitLab instances, and cloud service management interfaces.

Dependencies and Preconditions

Successful execution depends on several enabling conditions that determine whether the attack is feasible.

- Accessible authentication interface — no WAF, geo-blocking, or CAPTCHA enforcement

- Password reuse or weak composition — users selecting predictable credentials

- Lack of credential lockout or throttling — rate limits too high or absent

- Limited visibility into failed login telemetry — detection gaps in SIEM or cloud logs

Attackers often perform mass reconnaissance before attempting authentication. They use tools like Shodan, Censys, and Masscan to identify live services with open ports and login pages and map those targets to high-probability dictionaries built from past breaches.

Post-Access Activity

A successful dictionary attack merely unlocks the door. Once authenticated, the attacker typically:

- Harvests session tokens or elevates privileges through misconfigured roles

- Moves laterally using the same credentials on other systems via RDP, SSH, or VPN

- Deploys persistence through OAuth token registration, backdoor accounts, or API key generation

- Collects data from email, cloud storage, or internal dashboards

In cases where MFA blocks access post-login, attackers pivot. They may deliver phishing payloads tailored to MFA bypass, scrape session cookies via token theft, or exploit poor MFA fallback workflows to escalate.

Integration with Other Tactics

Dictionary attacks rarely operate in isolation. They intersect with multiple kill chain stages:

- Reconnaissance: Attackers fingerprint login pages and authentication technologies before launching the attack. Tools like WhatWeb and Wappalyzer help tailor the approach.

- Credential harvesting: Phishing campaigns or infostealers feed dictionary attacks by supplying usernames for validation.

- Persistence and command/control: Access gained via dictionary attacks often supports later-stage malware implants or data exfiltration over authenticated channels.

- Defense evasion: To avoid detection, attackers blend login attempts across time and IP addresses, rotate user-agent headers, and mimic human interaction patterns.

In hybrid environments, attackers may first compromise a low-privilege user account through dictionary attack, then use that access to query group memberships, escalate via cloud roles, and impersonate privileged identities.

Dictionary Attack in the Real World

Dictionary attacks continue to feature prominently in real-world breaches, especially where weak authentication policies intersect with public-facing services. While often overshadowed by zero-days and ransomware, these attacks remain foundational in campaigns targeting identity, access, and control.

Credential Abuse at Scale in CitrixBleed Fallout

In late 2023, the CitrixBleed vulnerability (CVE-2023-4966) exposed session token leakage in Citrix Gateway appliances. Attackers capitalized on the incident by pairing harvested session data with targeted dictionary attacks to compromise additional administrator accounts. Many organizations had lax secrets management, failing to rotate passwords or enforce MFA, which allowed access reuse against known usernames.

The U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) warned that advanced persistent threat (APT) actors used these dictionary-driven access attempts to pivot laterally into VPN infrastructure and cloud management planes. In sectors like healthcare and education, where legacy access policies remained in place, attackers gained persistent administrative footholds without triggering anomaly detection.

ZoomInfo Breach and SaaS Panel Targeting

In August 2023, threat actor "IntelBroker" claimed responsibility for breaching ZoomInfo by performing a credential-based attack against a publicly exposed administrative panel. ZoomInfo confirmed that the attacker gained access using a dictionary attack against login credentials, validating a leaked username and iterating password guesses from previously breached corpuses.

Although MFA was eventually enforced, the attacker successfully exfiltrated partial customer datasets before detection. The data breach underscored how dictionary attacks bypass control layers when session token capture or weak password reuse occur in tandem.

Industry-Wide Exploitation with Cloud Misconfiguration and IAM Abuse

IBM's X-Force Threat Intelligence Index for 2024 cited password-guessing techniques, including dictionary attacks, as one of the top three initial access vectors observed in cloud intrusions. Attackers routinely used dictionary scripts against exposed cloud login portals (e.g., Azure AD and AWS IAM) with success rates tied directly to policy leniency and user behavior.

Organizations in the financial sector, where staff often manage multiple environments through legacy credentials, were particularly vulnerable. In several red team assessments, testers gained access to production CI/CD environments by using environment-specific usernames and password lists derived from previous engagements or OSINT.

Dictionary Attack Detection and Indicators

Dictionary attacks generate unique behavioral and forensic artifacts — if you know where to look. They rarely involve malware or persistence mechanisms in the initial phase. Detection relies on telemetry, context, and well-tuned baselines.

Observable Indicators in Authentication Logs

Most dictionary attacks begin with large volumes of authentication attempts targeting the same user or endpoint. They often follow deterministic patterns that differ from legitimate user behavior.

- Burst patterns: Dozens or hundreds of login attempts in short intervals, often spaced by milliseconds or seconds

- Monotonic username targeting: Repeated attempts on a single account with varied passwords

- User-agent spoofing: Unusual or randomly generated user-agent strings in HTTP headers

- Sessionless activity: Lack of associated cookie reuse, consistent token regeneration, or valid device fingerprints

- Uncommon geo-IP origins: Requests from cloud providers or foreign countries not associated with business operations

- Consistent POST body structure: Identical parameter ordering and payload formatting across attempts

When attackers use distributed infrastructure, the source IPs may rotate. In such cases, defenders should correlate on the username or endpoint path rather than origin address alone.

Behavioral Patterns at Scale

Even distributed dictionary attacks — those performed across botnets or cloud microservices — exhibit consistency in intent.

- Lack of follow-up: No typical user actions post-login (e.g., no navigation, no token exchange, no session continuity)

- Failed MFA follow-through: After a successful password entry, the actor fails to complete MFA or retries from a new source

- Password spraying correlation: Login attempts use the same passwords across different usernames, if password reuse attacks operate in parallel

- Time-of-day anomalies: Credential attempts outside expected access hours, especially in tightly scheduled environments like healthcare or finance

In hybrid identity systems, attackers may jump across SSO providers, attempting identical credentials in Okta, Azure AD, or legacy LDAP portals.

Detection in SIEM and XDR Platforms

SIEM and XDR platforms can detect dictionary attacks with tailored correlation logic, provided authentication telemetry is centralized and accessible.

High-fidelity detection queries include:

- Repeated login attempts by username within a five-minute window exceeding a threshold (e.g., more than 15 failures)

- Unique source IPs targeting a single username across a defined period (distributed attack indicator)

- Identical request payloads (body, headers, method) with varying credentials from multiple origins

- Excessive HTTP 401 or 403 responses from a single client or to a single endpoint path

Enriching Detection with Context

Raw indicators rarely surface meaningful alerts without context. Correlating login failures can reduce false positives while elevating confidence scores. Correlations might include:

- Device posture

- Session replay anomalies

- Geographic profile mismatches

- Impossible travel logic

- Known credential dumps in threat intel feeds

Security teams should also tune UEBA (User and Entity Behavior Analytics) platforms to flag credential use that diverges from behavioral baselines.

Preventing and Mitigating Dictionary Attack

Effective defense against dictionary attacks requires layered safeguards across authentication logic, identity infrastructure, and perimeter visibility. Security leaders must implement controls that interrupt both the brute-force mechanism and the credential validation path. Relying on password complexity policies alone will not stop a determined adversary equipped with automation.

Harden Authentication Surfaces

Authentication endpoints must tolerate legitimate user behavior while remaining hostile to automated guessing. Design authentication workflows to disrupt enumeration and slow down credential testing without degrading usability. Critical code and configuration controls include:

- Lockout thresholds: Temporarily disable login after a set number of failed attempts. Tie lockouts to IP, user, and device fingerprint to reduce evasion.

- Dynamic rate limiting: Apply progressive backoff on repeated failures. Use reputation scoring to prioritize restrictions (e.g., block traffic from known Tor exit nodes or untrusted countries).

- Credential stuffing detection logic: Track high-velocity POSTs with varying usernames but identical passwords to catch horizontal dictionary attacks.

- Error response uniformity: Return identical HTTP status codes and body content for all authentication failures. Never disclose whether the username is valid.

- Session-aware CAPTCHA: Introduce CAPTCHA challenges only after anomalous behavior. Avoid default CAPTCHA on first request. It signals the presence of an authentication surface.

Avoid implementing login rate limiting in frontend JavaScript or on the client side. Enforcement must occur server-side or at the reverse proxy.

Strengthen Identity Systems

While password composition rules have diminishing returns, identity infrastructure can block attacks before passwords even matter. Essential IAM and MFA strategies include:

- Mandatory MFA on all externally exposed systems: Support TOTP, hardware keys (FIDO2/WebAuthn), or mobile push.

- Passwordless options for privileged users: Reduce reliance on memorized secrets. Use identity-bound tokens or biometric-backed authentication.

- Credential hygiene enforcement: Prevent reuse of previous passwords. Block known compromised passwords using NIST guidelines or Have I Been Pwned API integration.

- Admin interface isolation: Restrict administrative panels by source IP, VPN requirement, or private access gateway. Avoid exposing SaaS admin consoles to the open internet.

- Service account lockdown: Rotate secrets regularly, enforce strong entropy, and monitor nonhuman login patterns.

Relying on password complexity rules without MFA gives a false sense of security. Attackers adapt faster than password policy updates.

Network-Level Interruption

Blocking dictionary attacks at the edge buys time for detection and slows adversary progress. Implement layered controls that make credential guessing costly and time-consuming. Tactical network and segmentation controls include:

- Geo-IP access policies: Block countries outside operational zones unless explicitly required.

- Reverse proxies and WAFs with behavioral detection: Use anomaly detection to block unusual login frequency, parameter misuse, or replayed headers.

- Private ingress for sensitive apps: Require authentication gateways before reaching the actual login service.

- Cloud perimeter segmentation: Isolate critical services behind access brokers. Don’t allow direct-to-resource authentication from public IPs.

- Service exposure audits: Continuously scan for forgotten portals — admin UIs, test environments, legacy endpoints.

Organizational Controls and Human Factors

Attackers don’t need advanced tools when organizations fail to educate users or enforce accountability. Human-centric mitigations include:

- Security awareness campaigns: Focus on password managers, MFA enrollment, and phishing-resistant login practices.

- Policy enforcement tooling: Prevent credential reuse across environments. Use browser plugins or endpoint agents to alert on shared secrets.

- Access governance audits: Review user access regularly. Remove dormant accounts and tightly scope third-party roles.

- Red team simulation: Conduct regular password-guessing assessments using real-world dictionaries against staging systems.

What Doesn’t Work

- Frequent password changes: Rotating passwords every 60 or 90 days increases reuse and weakens user behavior.

- Overly complex password requirements: Enforcing arbitrary character mixes leads users to create predictable patterns attackers can exploit.

- Static CAPTCHA challenges: Static CAPTCHAs are bypassed easily with OCR, human farms, or pretrained models.

- IP-based blacklisting alone: IPs rotate. Without behavioral context, blacklists offer little defense.

Effective prevention doesn’t rely on a single choke point. It assumes credential guessing will occur and designs the system to limit its success, surface its presence, and contain its blast radius.

Attack Response and Recovery

Organizations that detect or confirm a successful dictionary attack must respond with urgency and precision. The response should eliminate the adversary’s foothold, restore the integrity of identity systems, and close systemic gaps that enabled the intrusion.

Contain and Disrupt Ongoing Access

First responders must act to halt further credential testing or account misuse without tipping off the attacker too early. Rapid containment limits escalation while preserving forensic data.

- Revoke active sessions: Invalidate tokens, API keys, and session cookies associated with compromised accounts.

- Block attack infrastructure: Use IP enrichment, header analysis, or geolocation to identify and block active sources via WAF or firewall policies.

- Enable forced password resets: Require resets on all accounts touched during the attack, prioritizing any that showed successful logins or follow-on activity.

- Enforce MFA immediately: Where supported, require MFA enrollment before reauthentication. Don’t wait for planned rollouts.

- Audit failed attempts: Identify other usernames targeted to detect which accounts may be next in line or part of a broader credential stuffing campaign.

If attackers exploited service accounts, rotate all affected credentials and check downstream integrations for anomalous activity.

Coordinate the Right Teams and Tools

Response requires more than containment — it demands coordinated action across engineering, infrastructure, and security leadership.

- Security operations: Lead log analysis, detect lateral movement, and manage external intelligence inputs.

- Identity and access teams: Validate IAM integrity, reset affected credentials, and verify MFA enforcement across the environment.

- Infrastructure teams: Review edge device logs, apply emergency ACLs, and harden exposed authentication surfaces.

- Legal and compliance: Determine if breached accounts involved regulated data. If so, prepare disclosure workflows.

- Incident response tools: Use SIEM, SOAR, and UEBA platforms to automate enrichment, timeline generation, and indicator propagation. Consider EDR or cloud workload protection tools if attacker persistence is suspected.

Execute a Targeted Post-Incident Review

A dictionary attack rarely exposes only one weakness. Organizations must review what the attacker exploited and why detection failed.

- Map the attack path: Reconstruct each step from initial request to final action. Determine where detection or response lagged.

- Correlate with known data breaches: Check whether compromised credentials matched previous breach corpuses or credential dumps.

- Audit MFA coverage: Quantify gaps across user types, applications, and access pathways.

- Review logging visibility: Confirm whether authentication telemetry was collected, normalized, and monitored at the time of attack.

- Run retrospective detections: Test updated detection logic against past logs to uncover similar undetected attempts.

- Conduct tabletop exercises: Simulate a credential-based attack and intrusion to evaluate decision-making and communication under pressure.

Harden Identity Surfaces After Recovery

Recovery without reform guarantees recurrence. Once secure, organizations must redesign authentication exposure.

- Block unauthenticated access to admin interfaces and legacy login portals.

- Sunset password-based access where token or certificate-based auth is viable.

- Align service accounts with least-privileged access, using scoped credentials and rotation automation.

- Integrate cyber threat intelligence feeds into identity telemetry to enrich login events with breach exposure context.

Dictionary Attack FAQs

Credential stuffing and credential spraying both involve unauthorized login attempts using compromised credentials, but the two attack methods differ.

Credential stuffing uses large sets of breached username-password pairs and attempts to log in across many services. Attackers rely on password reuse, targeting known combinations per user across multiple platforms.

Credential spraying uses a small number of common passwords — like Welcome123 or Spring2024! — against many usernames. It avoids account lockouts by spreading attempts thinly across users.

Unsalted hashing refers to hashing a password without adding a unique, random value (a salt) before the hash function processes it. When a system stores unsalted password hashes, identical passwords produce identical hashes, making them vulnerable to precomputed attacks like rainbow tables or simple dictionary matching. For example:

- The password "Password123" always produces the same hash.

- If two users choose "Password123", their stored hashes will match exactly.

Without salting:

- Attackers can build lookup tables in advance to reverse hashes quickly.

- Leaked hashes become immediately useful across systems using the same hash algorithm.

- Large-scale breaches become more damaging because hash collisions reveal user behavior.

Salting adds a user-specific random string to the password before hashing, so even identical passwords generate different hashes. Most modern systems combine salting with key stretching algorithms like bcrypt, scrypt, or Argon2 to slow down guessing attempts and neutralize dictionary-based hash cracking.