-

What Is a Cyber Attack?

- Threat Overview: Cyber Attacks

- Cyber Attack Types at a Glance

- Global Cyber Attack Trends

- Cyber Attack Taxonomy

- Threat-Actor Landscape

- Attack Lifecycle and Methodologies

- Technical Deep Dives

- Cyber Attack Case Studies

- Tools, Platforms, and Infrastructure

- The Effect of Cyber Attacks

- Detection, Response, and Intelligence

- Emerging Cyber Attack Trends

- Testing and Validation

- Metrics and Continuous Improvement

- Cyber Attack FAQs

- Dark Web Leak Sites: Key Insights for Security Decision Makers

-

What Is a Zero-Day Attack? Risks, Examples, and Prevention

- Zero-Day Attacks Explained

- Zero-Day Vulnerability vs. Zero-Day Attack vs. CVE

- How Zero-Day Exploits Work

- Common Zero-Day Attack Vectors

- Why Zero-Day Attacks Are So Effective and Their Consequences

- How to Prevent and Mitigate Zero-Day Attacks

- The Role of AI in Zero-Day Defense

- Real-World Examples of Zero-Day Attacks

- Zero-Day Attacks FAQs

-

What Is Lateral Movement?

- Why Attackers Use Lateral Movement

- How Do Lateral Movement Attacks Work?

- Stages of a Lateral Movement Attack

- Techniques Used in Lateral Movement

- Detection Strategies for Lateral Movement

- Tools to Prevent Lateral Movement

- Best Practices for Defense

- Recent Trends in Lateral Movement Attacks

- Industry-Specific Challenges

- Compliance and Regulatory Requirements

- Financial Impact and ROI Considerations

- Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Lateral Movement FAQs

-

What is a Botnet?

- How Botnets Work

- Why are Botnets Created?

- What are Botnets Used For?

- Types of Botnets

- Signs Your Device May Be in a Botnet

- How to Protect Against Botnets

- Why Botnets Lead to Long-Term Intrusions

- How To Disable a Botnet

- Tools and Techniques for Botnet Defense

- Real-World Examples of Botnets

- Botnet FAQs

- What is a Payload-Based Signature?

-

What is Spyware?

- Cybercrime: The Underground Economy

-

What Is Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)?

- XSS Explained

- Evolution in Attack Complexity

- Anatomy of a Cross-Site Scripting Attack

- Integration in the Attack Lifecycle

- Widespread Exposure in the Wild

- Cross-Site Scripting Detection and Indicators

- Prevention and Mitigation

- Response and Recovery Post XSS Attack

- Strategic Cross-Site Scripting Risk Perspective

- Cross-Site Scripting FAQs

- What Is a Dictionary Attack?

- What Is a Credential-Based Attack?

-

What Is a Denial of Service (DoS) Attack?

- How Denial-of-Service Attacks Work

- Denial-of-Service in Adversary Campaigns

- Real-World Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Detection and Indicators of Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Prevention and Mitigation of Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Response and Recovery from Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Operationalizing Denial-of-Service Defense

- DoS Attack FAQs

- What Is Hacktivism?

- What Is a DDoS Attack?

-

What Is CSRF (Cross-Site Request Forgery)?

- CSRF Explained

- How Cross-Site Request Forgery Works

- Where CSRF Fits in the Broader Attack Lifecycle

- CSRF in Real-World Exploits

- Detecting CSRF Through Behavioral and Telemetry Signals

- Defending Against Cross-Site Request Forgery

- Responding to a CSRF Incident

- CSRF as a Strategic Business Risk

- Key Priorities for CSRF Defense and Resilience

- Cross-Site Request Forgery FAQs

- What Is Spear Phishing?

-

What Is Brute Force?

- How Brute Force Functions as a Threat

- How Brute Force Works in Practice

- Brute Force in Multistage Attack Campaigns

- Real-World Brute Force Campaigns and Outcomes

- Detection Patterns in Brute Force Attacks

- Practical Defense Against Brute Force Attacks

- Response and Recovery After a Brute Force Incident

- Brute Force Attack FAQs

- What is a Command and Control Attack?

- What Is an Advanced Persistent Threat?

- What is an Exploit Kit?

- What Is Credential Stuffing?

- What Is Smishing?

-

What is Social Engineering?

- The Role of Human Psychology in Social Engineering

- How Has Social Engineering Evolved?

- How Does Social Engineering Work?

- Phishing vs Social Engineering

- What is BEC (Business Email Compromise)?

- Notable Social Engineering Incidents

- Social Engineering Prevention

- Consequences of Social Engineering

- Social Engineering FAQs

-

What Is a Honeypot?

- Threat Overview: Honeypot

- Honeypot Exploitation and Manipulation Techniques

- Positioning Honeypots in the Adversary Kill Chain

- Honeypots in Practice: Breaches, Deception, and Blowback

- Detecting Honeypot Manipulation and Adversary Tactics

- Safeguards Against Honeypot Abuse and Exposure

- Responding to Honeypot Exploitation or Compromise

- Honeypot FAQs

- What Is Password Spraying?

- How to Break the Cyber Attack Lifecycle

-

What Is Phishing?

- Phishing Explained

- The Evolution of Phishing

- The Anatomy of a Phishing Attack

- Why Phishing Is Difficult to Detect

- Types of Phishing

- Phishing Adversaries and Motives

- The Psychology of Exploitation

- Lessons from Phishing Incidents

- Building a Modern Security Stack Against Phishing

- Building Organizational Immunity

- Phishing FAQ

- What Is a Rootkit?

- Browser Cryptocurrency Mining

- What Is Cryptojacking?

What Is Pretexting?

Pretexting is a form of social engineering where attackers impersonate trusted entities to extract sensitive information or gain unauthorized access. It bypasses technical defenses by exploiting human trust, creating serious risk for executive access, internal systems, and the organization’s broader security posture.

Pretexting Explained

Pretexting is a cybercrime using a social engineering technique where adversaries invent and act out false identities to deceive targets into granting access, sharing credentials, or disclosing sensitive data. It belongs to the tactic of Initial Access in the MITRE ATT&CK framework and maps to T1201: Social Engineering. Unlike opportunistic phishing, pretexting is calculated, conversational, and often multistep.

Why Pretexting Demands Immediate Executive Attention

Pretexting has become a weapon of choice for adversaries seeking to circumvent hardened perimeters. Attackers blend behavioral psychology with reconnaissance to impersonate insiders, vendors, or authority figures, bypassing authentication protocols not through technical force but through persuasive deceit.

Sophisticated pretexting campaigns now leverage real-time data, generative AI, breached credentials, and organizational mapping to craft convincing narratives. These narratives bypass traditional email filters and fool even the most security-aware staff. What follows is often access to protected systems, executive calendars, financial workflows, or customer records.

For organizations with distributed teams, hybrid infrastructure, and complex supply chains, a single successful pretext can unravel layered defenses.

Strategic Risk Framing for the Boardroom

Pretexting can serve as a precursor to larger cyber attacks, including business email compromise (BEC), ransomware deployment, or insider threat insertion. Attackers target roles, not just systems. Executive assistants, procurement officers, and DevOps leads all hold access paths adversaries can manipulate.

Regulators and insurers are raising expectations around human risk controls, making resilience against pretexting a matter of fiduciary responsibility. Leaders must ask: Is our organization structurally and culturally resilient against deception-based threats?

The answer will define both your cybersecurity maturity and your organizational integrity in an era where trust is the new attack surface.

Evolution of the Attack Technique

Originally, pretexting relied on confidence tricks and human instinct. Attackers posed as IT staff, law enforcement, or executives. Today, they operate with enhanced realism:

- Leaked credentials and breach data inform their scripts.

- AI voice synthesis and deepfake visuals support impersonation across media.

- Cross-channel execution, from Slack to Zoom to mobile, sustains the illusion across workflows.

Pretexting has scaled in complexity and impact. Attackers now mirror corporate tone, reference real internal initiatives, and adapt dynamically during live interactions. It's no longer a one-off con. Pretexting is a persistent and adaptive access strategy designed to pierce organizational defenses by first compromising trust.

How Pretexting Works

Pretexting is a scenario-based attack that exploits human decision-making rather than system flaws. Attackers design and deliver believable narratives to elicit actions that would otherwise be denied. These could include granting access, transferring funds, or exposing sensitive information. The method hinges on realism, timing, and trust.

Step-by-Step Execution

Reconnaissance

Attackers collect OSINT, leaked credentials, and behavioral signals. Public social profiles, org charts, executive bios, supplier relationships, and even calendar metadata provide the insight needed to construct plausible narratives.

Pretext Development

The attacker crafts a scenario tailored to the target’s role and environment. Common personas include executives, auditors, vendors, or internal IT. Language, tone, and timing are adjusted to match organizational norms, often referencing real projects or pressure points.

Initial Engagement

Contact begins through a medium that supports the pretext. Tactics include:

- Email using spoofed or typo-squatted domains

- SMS messages mimicking internal tools or service providers

- VoIP calls with AI-generated voice cloning

- Chat interactions via Slack, Teams, or WhatsApp

- Deepfake-driven video calls in executive impersonation campaigns

Manipulation and Execution

The attacker leverages urgency and familiarity to override the target’s critical thinking. Common goals include:

- Harvesting credentials or MFA tokens

- Convincing the user to reset or delegate access

- Redirecting payments or exposing customer data

- Gaining remote access through “troubleshooting” tools

Post-Engagement Exploitation

After gaining access or data, the attacker may:

- Move laterally across SaaS environments or cloud platforms

- Register persistent access tokens or MFA devices

- Escalate privileges within IAM or ticketing systems

- Launch follow-on attacks such as BEC, ransomware, or data theft

Tools, Infrastructure, and Protocols

- VoIP and spoofing platforms: Used to falsify caller IDs or send bulk SMS

- Generative AI: Clones voices, simulates writing tone, and powers deepfake avatars

- Email impersonation kits: Preloaded with realistic executive personas

- Remote access utilities: Commonly used in “IT support” pretexts (e.g., AnyDesk, TeamViewer)

- Python and PowerShell scripts: Deployed post-access for lateral movement or data staging

Exploited Weaknesses

- Human layer: Role-based authority assumptions, urgency bias, overreliance on unverified channels

- Application layer: Weak or absent identity verification in SaaS platforms and IT helpdesk tools

- Cloud layer: Overprivileged IAM roles, unmonitored service account activity, weak configuration boundaries

- Network layer: Lack of segmentation or inspection on collaboration tools and email gateways

Real-World Variants

- Executive voice cloning: Attackers use AI to impersonate a CEO on a live call, instructing a finance lead to authorize a wire transfer.

- Fake vendor escalation: A threat actor mimics a known supplier, provides legitimate-looking documents, and requests access to shared folders or payment portal credentials.

- Helpdesk bypass: Attackers impersonate a remote employee and convince IT to reset MFA, citing urgency and impersonated approval from leadership.

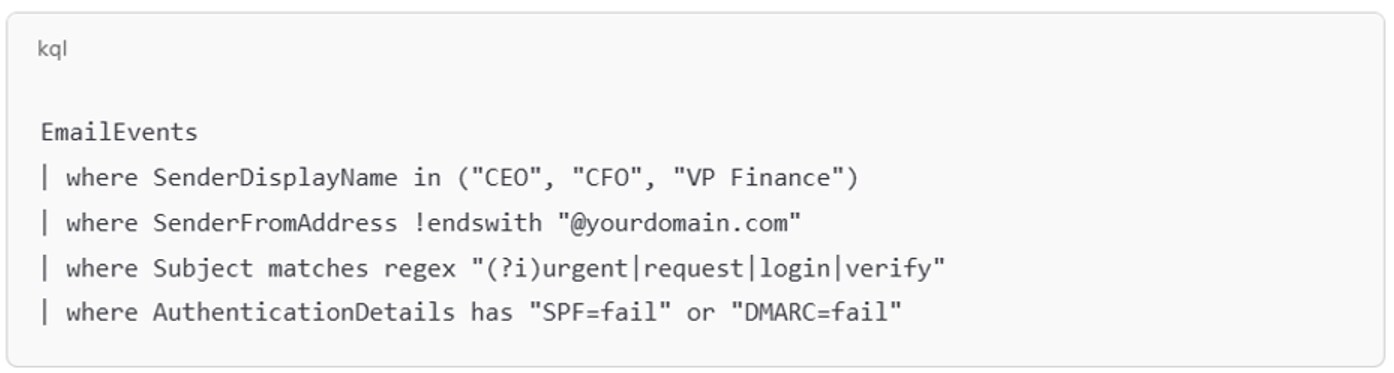

Figure 1: Detection Example: Microsoft Sentinel KQL Query

Pretexting isn’t opportunistic — it’s deliberate, researched, and often tailored to bypass controls without tripping alerts. Any security strategy that fails to address the human attack surface leaves the door wide open.

Integration in the Attack Lifecycle

A highly adaptive maneuver, adversaries use pretexting to sidestep technical barriers by inserting themselves into human decision points. Its strength lies in timing and placement. Deployed early, it opens the door. Used later, it accelerates privilege escalation, suppresses detection, or enables exfiltration without triggering alarms.

Entry Point into the Kill Chain

In most modern campaigns, pretexting enters during the initial access phase. It may precede or replace traditional phishing. Rather than lure a victim to click, the attacker engages them in a tailored conversation, often by impersonating someone inside the organization or a trusted third party. The objective is to compel an action — disclosing credentials, validating an MFA prompt, or provisioning temporary access.

When phishing fails due to hardened email security or awareness training, pretexting takes over. It doesn't require malware delivery or malicious URLs. It requires accuracy, patience, and context.

In advanced scenarios, pretexting follows credential theft or data discovery. The attacker might already possess access tokens or session cookies from earlier breaches and uses a fabricated scenario to legitimize their use or bypass secondary controls. For example, they might call a helpdesk and explain they’re locked out due to a device migration, using breached PII to authenticate and reset MFA.

Enablers and Dependencies

Pretexting thrives on situational intelligence. It relies on:

- Up-to-date data from data breaches, OSINT, and cloud misconfigurations

- Unmonitored communication channels (e.g., SMS, personal email, unmanaged collaboration tools)

- Gaps in identity verification, especially within helpdesk, finance, and DevOps workflows

- Cultural or operational assumptions, such as over-trusting executive directives or deprioritizing verification during high-volume service windows

In hybrid cloud environments, attackers often use pretexting to bridge identity gaps between on-premises and cloud services.

Role in Lateral Movement and Privilege Escalation

Once inside, pretexting becomes a tool for vertical or horizontal expansion. The attacker may impersonate a peer, supervisor, or vendor and initiate:

- Approval for elevated permissions

- Access to shared drives or CI/CD pipelines

- Disclosure of infrastructure documentation

- Enrollment of new devices or service accounts

Pretexting helps maintain stealth by keeping the operation “interactive” rather than overtly malicious. It reduces reliance on noisy techniques like brute force or privilege escalation exploits. In regulated industries, attackers often mimic auditors or compliance leads to harvest sensitive documents under a veneer of legitimacy.

Used to Sustain Access and Evade Detection

During the persistence phase, attackers can use pretexting to silently reinsert themselves into workflows. If credentials are revoked or sessions are flagged, they reengage support teams with plausible stories — lost phones, emergency access requests, or executive authorization — to reset or reissue permissions.

In parallel, they may use deepfake-enabled video calls or spoofed Slack profiles to keep the social engineering façade alive long enough to exfiltrate data or deploy malware.

Real-World Examples

Pretexting rarely makes headlines as the named root cause. It hides behind broader categories (e.g., phishing or business email compromise), yet it often forms the backbone of high-impact breaches. What distinguishes pretexting is not the toolset, but the social choreography. Attackers stage human trust as their entry point, their pivot path, or their means of erasing suspicion mid-operation.

Case Study: Scattered Spider and the Art of Believability

The threat group Scattered Spider gained notoriety in 2023 and 2024 for leveraging pretexting against telecom, gaming, and hospitality giants. Using phone calls and SMS messages, they impersonated employees and IT staff to bypass MFA, reset credentials, and embed remote tools within internal systems. These weren’t phishing emails — they were live, convincing human interactions conducted over real-time voice and chat channels.

In incidents involving MGM Resorts and Caesars Entertainment, attackers used pretexting to compromise IT helpdesks. Once in, they disabled security tools, accessed high-privilege accounts, and triggered ransomware deployment. The financial and operational impact was substantial:

- Caesars: Paid an estimated $15 million in ransom

- MGM: Suffered days of downtime, impacting reservations, check-ins, and slot machine functionality

These campaigns show how pretexting can serve as both the access mechanism and the enabling force behind persistence, escalation, and disruption.

Industry-Specific Targeting

Pretexting adapts to the culture and workflows of each sector:

- Healthcare: Attackers pose as auditors, legal counsel, or insurance reps requesting access to patient data or compliance systems. Pretexting is used to bypass access controls and pivot into EMR systems or medical device networks.

- Finance and Fintech: Common scenarios include impersonating regulators, auditors, or VIP clients. Attackers use urgency tied to compliance or market deadlines to override verification processes.

- SaaS and Tech: Engineering and DevOps teams are frequent targets. Pretexts reference sprint timelines, deployment rollbacks, or third-party audit coordination. The aim is access to CI/CD environments, cloud consoles, or credential vaults.

Across sectors, support desks and overworked staff remain the softest targets.

Operational Impact Metrics

- Detection difficulty: Pretexting often avoids detection by staying outside of traditional security controls — no malware, no links, no exploits.

- Attack dwell time: Interactions can last days or weeks as attackers nurture trust and exploit it gradually.

- Breach enablement: According to multiple post-incident forensics reports, up to 60% of successful BEC cases involved a form of pretexting at the identity verification stage.

- Cross-channel coordination: More than 40% of observed pretexting campaigns in 2024 involved two or more communication platforms, often combining phone, email, and chat.

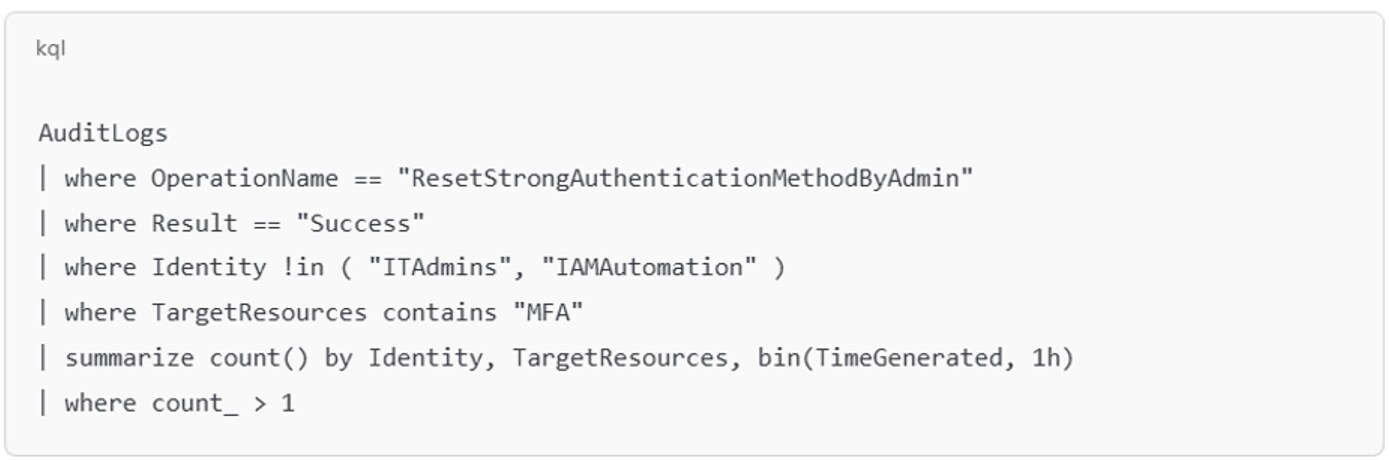

SOC teams monitoring for social engineering-based MFA resets can deploy behavioral rules using cloud SIEMs. Example Microsoft Sentinel KQL:

Figure 2: Detection Example of Helpdesk MFA Reset Pretext

Pretexting isn’t a low-tier tactic. It’s a force multiplier. In the hands of well-funded groups, it enables high-efficiency compromise without touching a line of perimeter code. As traditional defenses mature, social intrusion becomes the preferred breach vector. And in most cases, it works because the attacker sounds like they belong.

Pretexting Detection Tactics in Live Environments

Pretexting doesn’t announce itself with binaries or exploit code. It leaves traces only when social interaction intersects with system behavior. Attackers succeed not by breaking defenses but by persuading people to bypass them. Detecting pretexting requires telemetry that connects identity decisions — password resets, access grants, MFA changes — with contextual mismatches.

Traditional security tools often miss the early stages of pretexting. There's no link to scan, no attachment to sandbox, no signature to match. What appears is a pattern of interaction that feels legitimate — a user request, a helpdesk action, a workflow approval, but doesn’t align with expected behavior from that user, at that time, on that device.

Security information and event management (SIEM) and extended detection and response (XDR) platforms can catch these moments, but only if they're tuned to correlate identity events across platforms and flag anomalies in workflow execution. It's not about catching malware. It’s about noticing when trust has been misapplied.

Behavioral Markers of a Pretexting Attempt

Attackers using pretexting mimic internal communication patterns, but behavioral inconsistencies eventually emerge. A support request arrives from an employee who rarely contacts IT. The tone is urgent. The device is unfamiliar. Moments later, access is elevated, or an off-hours login is registered from a new geography.

Successful detection hinges on combining identity behavior, endpoint data, and workflow telemetry. Look for:

- Sudden bursts of administrative activity linked to a single identity

- Access attempts immediately following identity recovery or MFA reset

- Multiple failed identity validation attempts followed by success using minimal information

- Cross-platform handoffs, such as a request starting in Slack and ending with a helpdesk action

- Divergence between access channel and account norms — e.g., web access on a previously mobile-only account

The key is correlation. Pretexting doesn’t live in one log source. It becomes visible only when events are stitched together across cloud identity platforms, helpdesk systems, communication tools, and authentication telemetry.

Identity and Access Telemetry in SIEM and XDR

To catch pretexting in progress, defenders must operationalize anomaly detection around high-value identity operations. SIEM and XDR platforms should ingest signals from IAM, collaboration tools, and support workflows — not just endpoint and firewall logs.

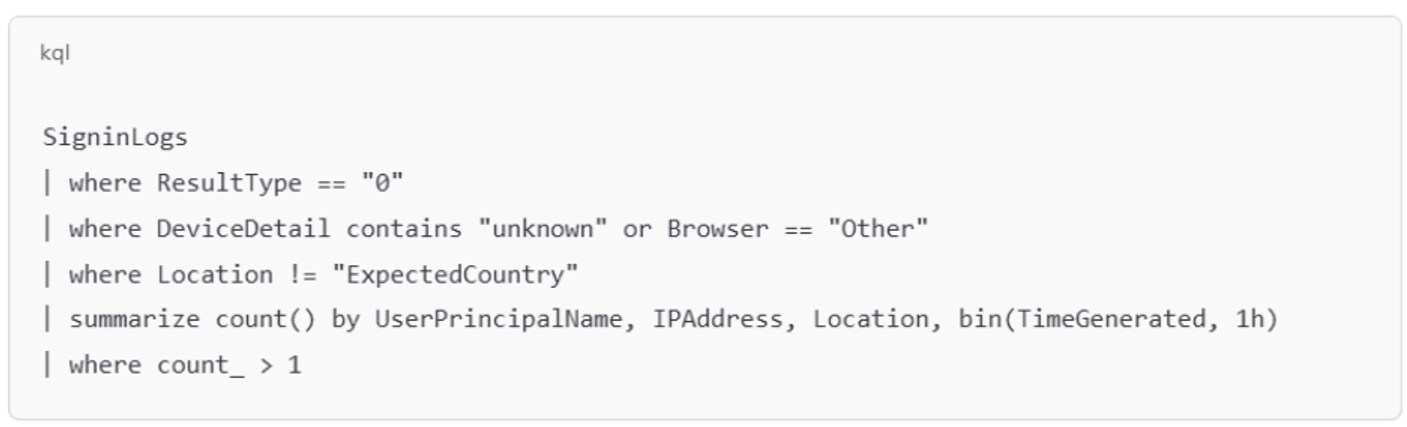

Signals worth instrumenting include:

- Administrative actions taken by support personnel, especially outside of standard change windows

- Password resets or MFA reconfigurations that precede lateral movement or privilege escalation

- Unusual IP-geolocation mismatches tied to login activity shortly after identity changes

- Device fingerprint changes or new browser agents associated with privileged accounts

- Workflow artifacts from ticketing systems that include keywords like “urgent,” “exec,” or “can’t wait”

Figure 3: Example suspicious login pattern

Why Signature-Based Detection Fails

Pretexting succeeds precisely because it avoids technical noise. There's no payload to hash. No command and control domain to track. No beacon to intercept. It’s persuasion, not malware. And that persuasion only works because defenders often ignore the intersection of human behavior and system state.

Detection must shift from artifact-first to context-first. Organizations need to monitor not just whether a change occurred, but how and why it occurred — who requested it, what channel they used, and whether that behavior matches the identity's history. Pretexting doesn’t impersonate a machine. It impersonates decision flow.

Prevention and Mitigation

Pretexting bypasses technical controls by targeting human judgment and process gaps. Preventing it requires defending where trust is assumed rather than verified. Effective mitigation starts with visibility into how access is granted, how authority is represented, and how people respond under pressure.

Hardening Access Control Systems

Attackers succeed when identity systems trust the request more than the context. Controls must treat all trust relationships, human or system, with suspicion.

- Enforce identity provenance: Use signed identity assertions for internal applications. Implement strict controls around identity federation and SSO token reuse, especially in hybrid cloud environments.

- Strengthen administrative workflows: Require multi-party approvals for any sensitive access change, including MFA resets, role elevation, or new device registration. These flows must be logged and monitored.

- Implement risk-based MFA: Adapt MFA challenges based on behavioral signals, such as device fingerprinting, access time anomalies, and geo-velocity. Don’t rely on SMS-based MFA, which is easily socially engineered.

- Control helpdesk privilege boundaries: Enforce Just-in-Time (JIT) permissions and limit what support staff can do without multi-factor validation and peer review. Record and monitor all privileged session activity.

- Rate-limit recovery actions: Impose throttling on account recovery, MFA resets, and access escalation. Pretexting often depends on urgency, which becomes ineffective if the system applies enforced delay.

Architectural Safeguards

Controls must operate at the boundaries of communication, access, and delegation.

- Isolate human-interactive services: Segment support interfaces, onboarding systems, and HR tools from core infrastructure. Pretexting often begins with abuse of these trusted systems.

- Monitor cross-platform behavior: Instrument collaboration tools and correlate with IAM logs. If a user is impersonated in Slack and a password reset follows in Okta, that sequence should raise a high-fidelity alert.

- Deploy UBA/UEBA at key identity chokepoints: Monitor for impossible travel, unusual admin actions, and deviations in helpdesk or IAM activity.

- Restrict token issuance windows: Limit session token lifetime and scope. Short expiration windows reduce the value of stolen or socially obtained credentials.

Policy and Process Defenses

Organizational culture must not allow urgency to override identity assurance.

- Codify no-exception identity protocols: No matter who calls, messages, or emails — support teams should require standard validation steps before taking action. Leadership must reinforce this expectation.

- Use known-channel callbacks: If a request originates via email or phone, mandate confirmation through a secondary, pre-established internal channel. Never respond directly through the originating medium.

- Maintain response checklists for high-risk interactions: Provide scripts for verifying identity and handling urgent access requests. This empowers employees to slow down without appearing resistant.

- Simulate targeted pretexting attempts: Go beyond phishing simulations. Emulate voice, video, and text-based impersonation attempts using real organizational context to expose gaps in both process and reflex.

What Doesn’t Work

- Generic security awareness training: Most programs focus on phishing and malware, not on high-context deception. Training that doesn’t include organizational-specific pretexts creates a false sense of readiness.

- Relying on technical indicators alone: Pretexting leaves no payload, no malicious file hash, and often no traceable domain. Detection must pivot toward correlating identity, behavior, and access timing.

- Assuming executives are exempt: Pretexting frequently targets senior leaders or their proxies. Any policy that allows exceptions at the top introduces systemic risk across the organization.