-

What Is a Cyber Attack?

- Threat Overview: Cyber Attacks

- Cyber Attack Types at a Glance

- Global Cyber Attack Trends

- Cyber Attack Taxonomy

- Threat-Actor Landscape

- Attack Lifecycle and Methodologies

- Technical Deep Dives

- Cyber Attack Case Studies

- Tools, Platforms, and Infrastructure

- The Effect of Cyber Attacks

- Detection, Response, and Intelligence

- Emerging Cyber Attack Trends

- Testing and Validation

- Metrics and Continuous Improvement

- Cyber Attack FAQs

- Dark Web Leak Sites: Key Insights for Security Decision Makers

-

What Is a Zero-Day Attack? Risks, Examples, and Prevention

- Zero-Day Attacks Explained

- Zero-Day Vulnerability vs. Zero-Day Attack vs. CVE

- How Zero-Day Exploits Work

- Common Zero-Day Attack Vectors

- Why Zero-Day Attacks Are So Effective and Their Consequences

- How to Prevent and Mitigate Zero-Day Attacks

- The Role of AI in Zero-Day Defense

- Real-World Examples of Zero-Day Attacks

- Zero-Day Attacks FAQs

-

What Is Lateral Movement?

- Why Attackers Use Lateral Movement

- How Do Lateral Movement Attacks Work?

- Stages of a Lateral Movement Attack

- Techniques Used in Lateral Movement

- Detection Strategies for Lateral Movement

- Tools to Prevent Lateral Movement

- Best Practices for Defense

- Recent Trends in Lateral Movement Attacks

- Industry-Specific Challenges

- Compliance and Regulatory Requirements

- Financial Impact and ROI Considerations

- Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Lateral Movement FAQs

-

What is a Botnet?

- How Botnets Work

- Why are Botnets Created?

- What are Botnets Used For?

- Types of Botnets

- Signs Your Device May Be in a Botnet

- How to Protect Against Botnets

- Why Botnets Lead to Long-Term Intrusions

- How To Disable a Botnet

- Tools and Techniques for Botnet Defense

- Real-World Examples of Botnets

- Botnet FAQs

- What is a Payload-Based Signature?

-

What is Spyware?

- Cybercrime: The Underground Economy

-

What Is Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)?

- XSS Explained

- Evolution in Attack Complexity

- Anatomy of a Cross-Site Scripting Attack

- Integration in the Attack Lifecycle

- Widespread Exposure in the Wild

- Cross-Site Scripting Detection and Indicators

- Prevention and Mitigation

- Response and Recovery Post XSS Attack

- Strategic Cross-Site Scripting Risk Perspective

- Cross-Site Scripting FAQs

- What Is a Dictionary Attack?

- What Is a Credential-Based Attack?

-

What Is a Denial of Service (DoS) Attack?

- How Denial-of-Service Attacks Work

- Denial-of-Service in Adversary Campaigns

- Real-World Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Detection and Indicators of Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Prevention and Mitigation of Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Response and Recovery from Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Operationalizing Denial-of-Service Defense

- DoS Attack FAQs

- What Is Hacktivism?

- What Is a DDoS Attack?

-

What Is CSRF (Cross-Site Request Forgery)?

- CSRF Explained

- How Cross-Site Request Forgery Works

- Where CSRF Fits in the Broader Attack Lifecycle

- CSRF in Real-World Exploits

- Detecting CSRF Through Behavioral and Telemetry Signals

- Defending Against Cross-Site Request Forgery

- Responding to a CSRF Incident

- CSRF as a Strategic Business Risk

- Key Priorities for CSRF Defense and Resilience

- Cross-Site Request Forgery FAQs

- What Is Spear Phishing?

- What is a Command and Control Attack?

- What Is an Advanced Persistent Threat?

- What is an Exploit Kit?

- What Is Credential Stuffing?

- What Is Smishing?

-

What is Social Engineering?

- The Role of Human Psychology in Social Engineering

- How Has Social Engineering Evolved?

- How Does Social Engineering Work?

- Phishing vs Social Engineering

- What is BEC (Business Email Compromise)?

- Notable Social Engineering Incidents

- Social Engineering Prevention

- Consequences of Social Engineering

- Social Engineering FAQs

-

What Is a Honeypot?

- Threat Overview: Honeypot

- Honeypot Exploitation and Manipulation Techniques

- Positioning Honeypots in the Adversary Kill Chain

- Honeypots in Practice: Breaches, Deception, and Blowback

- Detecting Honeypot Manipulation and Adversary Tactics

- Safeguards Against Honeypot Abuse and Exposure

- Responding to Honeypot Exploitation or Compromise

- Honeypot FAQs

- What Is Password Spraying?

- How to Break the Cyber Attack Lifecycle

-

What Is Phishing?

- Phishing Explained

- The Evolution of Phishing

- The Anatomy of a Phishing Attack

- Why Phishing Is Difficult to Detect

- Types of Phishing

- Phishing Adversaries and Motives

- The Psychology of Exploitation

- Lessons from Phishing Incidents

- Building a Modern Security Stack Against Phishing

- Building Organizational Immunity

- Phishing FAQ

- What Is a Rootkit?

- Browser Cryptocurrency Mining

- What Is Pretexting?

- What Is Cryptojacking?

What Is Brute Force?

Brute force is a high-volume cyber attack method that systematically guesses credentials or encryption keys until access is granted. It remains effective against weak authentication schemes and poorly configured services, exposing organizations to account takeover, service interruption, and downstream compromise of privileged infrastructure.

How Brute Force Functions as a Threat

Brute force is a technique used in cybercrime to compromise authentication systems by attempting every possible combination of credentials or keys until access is granted. It operates without prior knowledge of the correct value and depends entirely on repetition, speed, and the absence of effective rate-limiting defenses.

In the MITRE ATT&CK framework, brute force is tracked under T1110: Brute Force within the Credential Access tactic. It includes several sub-techniques — T1110.001 (Password Guessing), T1110.002 (Password Spraying), and T1110.003 (Credential Stuffing) — each describing variations in approach.

Unlike malware-based intrusion or exploit chains that target software flaws, brute force targets authentication logic and identity infrastructure. It bypasses complexity through persistence, not sophistication.

Terminology Commonly Associated with Brute Force

- Password guessing targets individual accounts using common or weak passwords.

- Password spraying reverses the approach — using a few popular passwords across many usernames to avoid lockouts.

- Credential stuffing relies on breached credentials reused across platforms, technically distinct but often paired with brute force-like automation.

- Key cracking applies brute force logic to encryption keys instead of passwords.

- Reverse brute force starts with a known password and attempts to match it against large username datasets.

These terms are not interchangeable. They describe how the attacker distributes guesses, chooses input data, and times execution.

How Brute Force Has Evolved

Early brute force attacks targeted local login screens or offline password hash dumps using tools like John the Ripper or Hydra. The process was noisy, slow, and detectable.

Attackers now weaponize automation through:

- Distributed infrastructures: Botnets and residential proxy networks rotate IPs to evade blocking.

- API abuse: Automated login attempts against web or mobile authentication endpoints, often disguised as legitimate traffic.

- Cloud-based cracking: GPU-accelerated virtual machines rented at scale to reduce time-to-crack on encrypted data or hashed credentials.

- Stealth tuning: Modern brute force campaigns throttle attempts to stay under alerting thresholds and mimic human-like interaction rates.

Authentication systems, especially in cloud and SaaS platforms, are increasingly under attack not because they are misconfigured, but because brute force operations have learned how to stay quiet, distributed, and persistent.

Brute force has outgrown its reputation as a crude or obsolete technique. It is now an adaptive, low-cost attack vector that probes the intersection of weak credentials, poor observability, and outdated identity assumptions. Any system that accepts user input without intelligent response handling remains a viable target.

How Brute Force Works in Practice

Brute force attacks succeed by turning speed and volume into access. The attacker does not require inside knowledge — only an entry point that accepts repeated input. Whether the target is an exposed login page, a VPN gateway, or a misconfigured API, the process follows a familiar pattern — identify a target, generate guesses, rotate infrastructure, and wait for a hit.

Brute force isn't inherently sophisticated, but its execution has matured. Modern campaigns often leverage distributed architectures, credential heuristics, and evasion-aware timing to extend dwell time and avoid triggering basic rate-limiting defenses.

Step-by-Step Execution of a Brute Force Attack

Target Enumeration

The attacker scans for authentication surfaces — SSH, RDP, SaaS login pages, VPN portals, or exposed APIs. Tools like Shodan, Censys, or Nmap are used to identify services and banner details. If targeting a known application, the attacker may focus on a specific URL or endpoint such as /login, /auth, or OAuth token requests.

Username Discovery

Usernames are harvested from OSINT sources, breached databases, GitHub commits, email metadata, or enumeration flaws. On some systems, responses differ subtly between valid and invalid usernames, allowing attackers to build precise targets.

Password Input Generation

Wordlists such as rockyou.txt, custom dictionaries, or Markov models are fed into automated tools. Passwords may be ordered by frequency, complexity, or likelihood based on user context.

Authentication Attempts

Requests are sent in bulk or in sequence using tools like Hydra, Medusa, Burp Intruder, or custom Python scripts. Attackers distribute traffic across proxies or botnets to evade IP-based rate limiting and reputation checks.

Feedback Parsing

Responses are analyzed for success indicators — redirects, status codes (e.g., 200 OK vs. 403 Forbidden), token issuance, or session cookies. Successful attempts are logged and either exploited immediately or sold to credential marketplaces.

Follow-On Access Or Escalation

Upon gaining access, attackers may enroll a secondary MFA device, exfiltrate sensitive data, or pivot to more privileged targets. Brute force is rarely the end goal — it’s the key to a larger compromise.

Common Tools and Protocols Used in Brute Force Attacks

- Hydra: A parallelized login cracker for dozens of protocols including SSH, FTP, HTTP, and RDP

- Medusa: Fast and flexible with modular login plugin support

- Ncrack: Developed by the Nmap project, optimized for network authentication cracking

- Burp Suite Intruder: Often used for brute force against web apps and APIs

- CURL, Python (requests), Selenium: Employed to script authentication workflows and bypass JavaScript-heavy frontends

- Tor, VPNs, rotating proxies: Used to mask attacker origin and prevent IP-based blocking

Protocols frequently targeted include SSH, SMB, RDP, LDAP, SMTP, HTTPS, and any application with an exposed login interface lacking enforcement controls.

Vulnerabilities and Layers Exploited by Brute Force

- Application layer: Unrestricted login attempts, predictable error messages, and lack of CAPTCHA or MFA

- Network layer: Insufficient segmentation, open management interfaces, and flat access to internet-facing services

- Identity and cloud layer: Poor credential hygiene, stale accounts, weak password policies, and missing behavior-based detection

- Human layer: Password reuse, weak password creation, and failure to report repeated lockouts or login anomalies

Brute force attacks don’t exploit flaws in code — they exploit misconfigurations, missing safeguards, and behavioral predictability.

Variants and Real-World Delivery Tactics

- Password spraying: Attempts a small list of common passwords across many usernames to avoid triggering account lockouts

- Reverse brute force: Uses a known weak password (e.g., "Welcome123") across a wide range of users

- Token brute forcing: Targets short-lived or poorly generated tokens in reset or activation links

- API brute force: Exploits rate-unrestricted endpoints, often bypassing front-end protections via direct HTTP requests

- Cloud console attacks: Focused on AWS, Azure, and GCP IAM login endpoints using known credentials or brute force against admin accounts

Brute force campaigns increasingly adapt to application architecture. Attackers script JavaScript rendering, mimic user-agent behavior, and maintain session state across retries to defeat more sophisticated defenses.

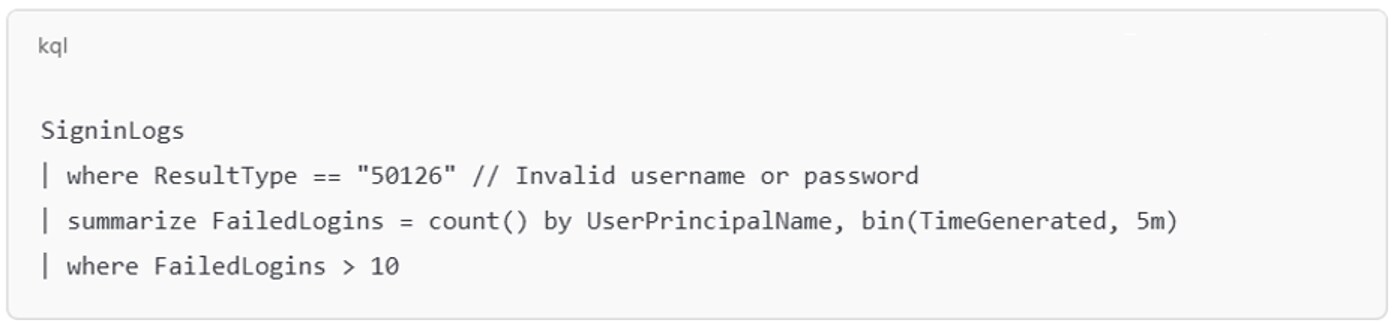

Image 1: Example of an Azure sign-in failure spike identifies accounts targeted by repeated failed logins over a short window, a strong signal of brute force or spraying activity.

Brute Force in Multistage Attack Campaigns

Brute force isn't a standalone threat. It operates as a utility function within broader adversary strategies, often serving as the first step in gaining access to internal environments. Whether automated or tightly targeted, brute force gives attackers a foothold — an authenticated session that unlocks downstream operations, from privilege escalation to data exfiltration.

The attack’s utility depends on its timing and pairing with other tactics. In some cases, it opens the door for initial compromise. In others, it revives access when a previously compromised account has been disabled. Brute force is the adversary’s universal skeleton key — inefficient alone, but lethal when paired with automation, context, and patience.

Role of Brute Force in the Kill Chain

In modern campaigns, brute force most commonly appears in the initial access phase. Adversaries use it to break into externally facing authentication portals — VPNs, remote desktops, webmail, or SaaS platforms. Once access is gained, they blend into the environment, often using the legitimate session to bypass endpoint controls and cloud telemetry.

If attackers already possess usernames or credential fragments — often collected via phishing, prior breach, or reconnaissance — they may use brute force to complete the credential pair. This variant reduces detection and dwell time by operating under the radar of known-credential alerts.

Following successful entry, brute force enables:

- Privilege escalation: Attackers may use the same technique internally to compromise administrator accounts, domain controllers, or service accounts if internal interfaces lack enforcement

- Lateral movement: Gained credentials may unlock file shares, collaboration platforms, or orchestration tools

- Persistence: If other mechanisms are lost, attackers return to brute force to reclaim access, especially against backup accounts or unmonitored third-party logins

- Exfiltration: In cloud environments, brute-forced accounts often lead directly to unstructured data storage or customer datasets, especially in flat-permissioned systems

Brute force may reappear at any stage of the operation where credentials serve as gates between segments.

Enabling Conditions and Dependencies

Brute force is only effective when the environment allows ungoverned repetition. Key enabling factors include:

- External services with weak or no rate limiting

- Identity platforms that lack behavioral baselining or device validation

- Shared or reused credentials across multiple services

- Uninstrumented interfaces such as legacy VPNs, dev/test environments, or partner portals

- Failure to monitor inactive or overprivileged accounts

Attackers prefer targets where input is cheap and output is deterministic. Brute force thrives on stability — login pages that don’t rotate, credentials that don’t expire, APIs that don’t throttle.

In the cloud, brute force often targets federated identity integrations or shadow administrative panels where username discovery is trivial and session issuance is loosely enforced.

Interplay with Other Techniques

Brute force rarely acts alone. It pairs with reconnaissance, spoofing, and automation frameworks to expand reach and reduce exposure.

- Post-phishing access: When attackers gain a username through phishing but not a password, brute force is used to complete the chain

- Credential stuffing follow-up: After credential reuse fails, attackers apply brute force to weak or guessable passwords across the same identities

- Post-exploitation pivoting: Once inside, attackers may brute force local admin credentials on lateral targets or escalate to domain-level control

- Evasion support: If endpoint protections disrupt malware payloads, brute-forced access allows persistence without code execution

Brute force doesn’t need to be sophisticated. It plays a supporting role across the entire intrusion lifecycle by enabling reliable entry, recovery, and movement without triggering the same alarms as exploit-based intrusion.

Any security program that assumes brute force only matters at the perimeter has already lost visibility into the center. Brute force is always in the room — it just changes its role depending on what the attacker needs next.

Real-World Brute Force Campaigns and Outcomes

Brute force remains a favored tactic not because it’s elegant, but because it works. When defenses lag behind attacker automation, brute force campaigns generate high return with low risk. In recent years, several notable breaches have traced their origins to brute force attacks that were overlooked, underestimated, or misunderstood.

Although brute force rarely earns the headline, it often serves as the root cause beneath credential-based intrusions, ransomware detonations, and persistent unauthorized access to cloud environments.

Campaign: 0ktapus and SaaS Identity Compromise

In 2022, a threat actor group known as 0ktapus used a combination of phishing and brute force to compromise over 130 organizations, including prominent names in SaaS, fintech, and crypto. Their approach combined:

- Credential phishing to harvest email addresses and phone numbers

- Brute force techniques to guess MFA codes or passwords where they were not phished

- Credential reuse attempts across internal systems and cloud platforms

The fallout included unauthorized access to customer data, tampering with internal DevOps environments, and persistent credential exposure across Slack, GitHub, and customer-facing portals.

What made 0ktapus significant was not the complexity of the intrusion — but how brute force amplified initial access into multi-org compromise. Brute force was used opportunistically whenever phishing failed.

Case Study: Citrix ADC Credential Spray (2023)

In late 2023, multiple healthcare and public sector organizations were targeted via Citrix ADC endpoints that lacked throttling protections. Attackers launched distributed password spraying campaigns, leading to several successful compromises of internal applications and VPN infrastructure.

- The attack used common passwords (e.g., Winter2023!, Welcome1) rotated across dozens of usernames

- Login attempts originated from a large residential proxy pool to avoid IP reputation checks

- Lateral movement occurred through SMB and RDP after credential reuse

Impacted organizations reported VPN outages, unauthorized data access, and — in at least one case — ransomware deployment attributed to access obtained through brute force.

Sector Focus: Finance and SaaS

Brute force attacks disproportionately target industries where authentication is abundant and enforcement is inconsistent.

- Finance: Online banking portals, brokerage APIs, and internal dashboards receive high volumes of automated login traffic, especially during tax seasons and quarterly close cycles

- SaaS: Customer-facing interfaces with customizable login flows are frequent targets, especially those that allow branded URLs (e.g., customername.vendor.com/login) or API-based auth flows

- Healthcare: Legacy portals tied to EMRs or claims processing platforms often lack MFA or lockout enforcement, making them attractive brute force targets

In each case, attackers know where password policies lag, where API throttling is absent, and where credentials are reused across interfaces.

Operational Metrics and Detection Challenges

- Frequency: Some large enterprises observe tens of thousands of brute force attempts daily across exposed endpoints

- Duration: Distributed attacks often run for weeks, remaining under alert thresholds by rotating IPs, devices, and request intervals

- Detection difficulty: When attackers throttle requests and mimic human behavior, standard login failure rules are too coarse to be effective

- Impact severity: In environments with weak password hygiene and no MFA, brute force remains one of the most efficient ways to achieve persistent access

Detection Patterns in Brute Force Attacks

Brute force attacks do not require stealth in a traditional sense — but they increasingly avoid obvious detection by spreading attempts across accounts, time windows, and infrastructure. The indicators exist, but they require correlation across identity, behavior, and network sources. Detecting brute force reliably demands a shift from volume-based alerting to context-aware monitoring of access behavior.

While brute force may originate from untrusted IP ranges or exhibit high-frequency login failures, well-resourced attackers blend traffic into routine authentication flows, making detection more about precision than volume.

Indicators in Network and Application Logs

Brute force attempts reveal themselves through inconsistencies in request origin, frequency, and success patterns. Even when attackers slow down, they often leave behind technical markers.

- IP reputation anomalies: Requests from anonymizing services, newly registered IPs, or residential proxy networks

- Unusual user-agent strings: Outdated or generic browser identifiers used by automated tools

- Header discrepancies: Missing or malformed headers (e.g., Referer, Origin, User-Agent) on interactive endpoints

- Geographic inconsistency: Multiple login attempts from distant regions within short time intervals

- Uniform resource targeting: Repeated authentication attempts on the same endpoint without variation (e.g., /auth/login, /token, /oauth2/authorize)

- Status code frequency: Spikes in 401 (Unauthorized), 403 (Forbidden), or 429 (Too Many Requests)

Many of these indicators remain invisible unless telemetry is normalized and aggregated across sources.

Behavioral Signatures of Brute Force Campaigns

Behavioral patterns provide higher-fidelity detection, particularly in mature environments where log noise is constant. Brute force campaigns, even those designed to evade traditional rate-based thresholds, often demonstrate:

- Low-success, high-attempt ratios across multiple usernames

- Account lockout clustering: Several lockouts occurring on similar usernames in tight time windows

- Credential replays: Reuse of the same password across different usernames in password spraying campaigns

- MFA challenge exhaustion: Repeated triggering of MFA prompts from unknown devices

- Timing cadence: Regular intervals between login attempts, revealing automation behind human-looking behavior

Attackers increasingly blend login timing to mimic user interaction. Detection logic must account for login context — not just count failed attempts.

SIEM and XDR Monitoring Recommendations

Detection effectiveness depends on the ability to pivot across identity, authentication, and infrastructure layers. SIEM and XDR platforms should ingest identity provider logs, application-level telemetry, and behavioral analytics. Priority indicators include:

- Login attempts across many accounts from a single IP or IP range

- Access attempts from multiple IPs targeting a single account

- Authentication attempts outside of normal working hours or geographic norms

- Repeated login attempts to API endpoints that bypass the front-end login UI

- MFA requests denied or ignored in rapid succession

Effective correlation rules should stitch together signals over longer windows than traditional IDS systems — brute force campaigns often operate just below detection thresholds, sometimes across days.

Practical Defense Against Brute Force Attacks

Brute force is a symptom of poor authentication design, not a clever adversary. Organizations that treat authentication as a front-line control — not a formality — eliminate most brute force risk. Effective prevention starts at the infrastructure level but must extend through identity design, policy enforcement, and user behavior. Attackers exploit input repetition; defenders must remove that option.

Security teams don’t need more complexity. They need consistent enforcement across every surface that accepts credentials. Whether it's an exposed login page or a forgotten SSO integration, the goal is simple: turn brute force into wasted effort.

Authentication Control at the Infrastructure Level

Systems that accept repeated input must be architected to resist automation.

- Rate limit all authentication endpoints: Apply adaptive throttling per user and per IP address. Back-off timers should increase with each failure.

- Implement credential lockouts with exponential delays: Lock accounts temporarily after a threshold of failed attempts. Avoid revealing lockout through error messaging.

- Use strong password complexity and length requirements: Reject short or commonly used passwords outright. Combine dictionary checks with entropy scoring.

- Disallow username enumeration: Ensure login responses are consistent regardless of whether the username exists or not. Error messages should not disclose account validity.

APIs should be treated with the same rigor. If they accept credentials or tokens, they require the same controls — rate limits, input validation, and behavioral monitoring.

Identity and Access Controls to Thwart Brute Force

The most effective way to defeat brute force is to render guessed credentials useless. This means decoupling credentials from direct access and requiring context-aware validation.

- Require phishing-resistant MFA everywhere: Hardware-backed WebAuthn (e.g., YubiKey, biometric auth) eliminates the value of a guessed password. Avoid SMS or email OTPs.

- Apply conditional access policies: Block or challenge logins based on geography, time of day, device fingerprint, or network origin.

- Enforce Just-in-Time access: Eliminate persistent credentials for sensitive roles. Access is granted only when needed and automatically revoked.

- Audit and remove stale accounts: Disable any inactive or dormant identities, especially those lacking MFA or assigned to deprecated services.

Identity protection must extend beyond the user — service accounts, automation tokens, and CI/CD credentials are frequent brute force targets due to lax policy enforcement.

Related Article: CICD-SEC-2: Inadequate Identity and Access Management

Segmentation and Network-Level Defenses

Brute force campaigns often succeed because authentication surfaces are overexposed or undersegmented. Tightening network access limits brute force scope.

- Restrict access to internal services using VPN, IP allowlists, or private links

- Monitor cloud provider logs for unauthenticated traffic surges

- Use web application firewalls (WAFs) with bot detection tuned for credential abuse

- Block known anonymizers and low-reputation IP ranges

- Instrument logs at the edge to detect enumeration attempts and abuse patterns

Modern segmentation should prioritize identity over static IPs, but that doesn’t mean ignoring origin. Even distributed brute force has an infrastructure footprint.

Policy and User Behavior Considerations

While technology handles most of the heavy lifting, users remain a critical layer in preventing brute force from evolving into full compromise.

- Set explicit lockout thresholds and recovery processes: Users should know what to expect if they trigger a lockout and how to safely recover.

- Train helpdesk teams to detect scripted recovery requests: Attackers often follow brute force with social engineering to bypass controls.

- Prohibit password reuse across internal services: Use automated tooling to flag repeated patterns across domains or apps.

- Include brute force simulation in red team exercises: Many organizations overestimate their detection fidelity when faced with slow, distributed attempts.

No amount of training replaces a strong identity architecture, but human awareness remains a valuable buffer against oversights and escalation.

Common Missteps That Undermine Brute Force Defense

- Relying on CAPTCHA: Most CAPTCHA systems are bypassed by bots or solved by humans in click farms. CAPTCHA alone isn't a brute force deterrent.

- Using weak MFA like SMS: SMS OTPs are susceptible to phishing, SIM swap attacks, and MFA fatigue tactics.

- Assuming cloud providers protect everything: Identity enforcement is a shared responsibility. Misconfigured IAM roles, unmanaged OAuth apps, and open admin consoles still require customer-side hardening.

- Focusing only on the perimeter: Internal interfaces, legacy apps, and development systems often remain unprotected and exploitable.

Response and Recovery After a Brute Force Incident

Brute force attacks often appear low-grade or routine, but the moment they succeed, they become gateways to far-reaching compromise. Organizations that treat brute force detection as an early-stage intrusion event, rather than just a failed login spike, respond faster and contain lateral movement more effectively.

The key to responding is to act decisively on the assumption that any successful brute force event signals a broader access strategy. Passwords are not the end goal. They are a means to impersonate, persist, and exfiltrate. Every recovery plan must reflect that.

Containment of Brute Force Intrusions

Response begins with identity. Containment must prioritize invalidating compromised access and halting automated input.

- Force credential resets for any accounts targeted and verified as compromised

- Revoke active sessions across identity providers, VPNs, and SaaS platforms where brute-forced accounts are valid

- Block IP addresses or IP ranges associated with high-volume or distributed attempts

- Harden login endpoints immediately by enabling MFA, tightening lockout policies, and applying geo-IP restrictions

- Audit authentication logs across applications and infrastructure to identify additional targets or access attempts

Containment isn't limited to identity platforms. If brute force leads to credential reuse or privilege escalation, EDR systems and cloud consoles may also need to isolate impacted resources or accounts.

Eradication and Root Cause Analysis

Eradication isn't complete until every affected credential, session, and token is accounted for. Brute force can compromise more than users. It can affect service accounts, access keys, and integration tokens.

- Invalidate API keys and automation credentials exposed through brute-forced accounts

- Re-enroll MFA where attacker-enrolled devices or recovery options may have been tampered with

- Check for secondary persistence mechanisms, such as OAuth grants, authorized apps, or staged access tokens

- Patch login systems or interfaces that permitted the attack due to misconfiguration (e.g., no rate limiting, weak password policies)

Eradication should also extend to infrastructure monitoring, ensuring attack tooling has not installed backdoors, web shells, or unauthorized agents.

Coordination Across Security and Business Functions

Response to brute force involves more than the SOC. Effective containment and recovery require fast coordination with:

- IAM teams, to manage revocation, access revalidation, and user communication

- IT and endpoint operations, to verify session termination, secure endpoints, and remove unauthorized tools

- Legal and compliance, to assess reporting requirements and contractual impacts

- Communications or HR, if employee accounts were compromised and notifications are warranted

- Incident response or forensic partners, if activity suggests deeper compromise beyond the authentication layer

Brute force often exposes process gaps, especially when recovery relies on legacy password reset procedures or under-instrumented systems.

Post-Mortem and Long-Term Hardening

Every brute force incident should trigger a review of identity architecture, logging coverage, and detection logic.

- Review all identity telemetry for missed indicators: Where was the first anomaly? How was it escalated?

- Test controls against similar attack patterns: Can the current system detect slow, distributed attempts or password spray campaigns?

- Update credential policies to require stronger entropy and eliminate static secrets where possible

- Ensure all authentication surfaces are enrolled in centralized monitoring, including staging environments, partner portals, and legacy tools

- Integrate brute force simulations into future red team exercises to validate both prevention and response workflows

A brute force attack doesn’t end when the password is changed. It ends when the system, the telemetry, and the culture are no longer susceptible to credential-based intrusion.